Record floods and droughts fuelled by the El Niño and La Niña phenomena around the globe, from Australia to west Africa and the US to Argentina, are expected to become further intensified by climate change by 2030, according to the latest scientific reports.

A new study published in Nature concluded that the influence of a warming planet in pushing up ocean temperatures in the eastern Pacific will be detectable in the weather patterns in eight years — almost 70 years earlier than previously thought.

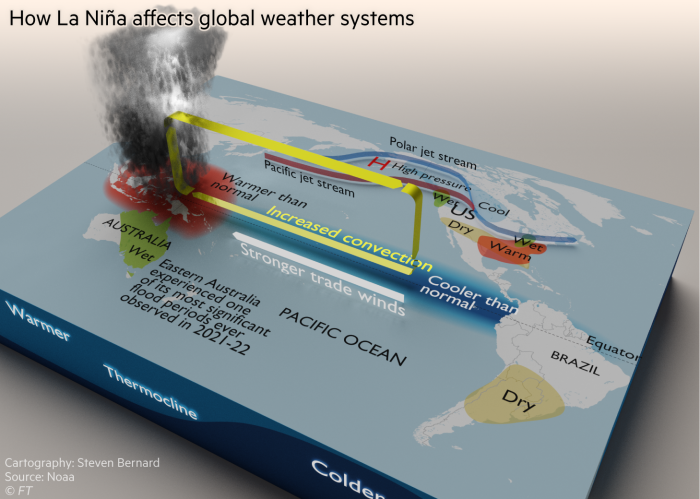

The La Niña phenomenon, which involves a large-scale cooling of the Pacific Ocean’s surface, drives changes in wind and rainfall patterns around the world. Typically, the pattern drives more rain in parts of Asia, including Australia, and drier conditions in parts of the US, South America and Africa.

At present, the world is experiencing the first “triple dip” La Niña weather pattern in more than 20 years, exacerbating patterns of flooding and drought in some countries.

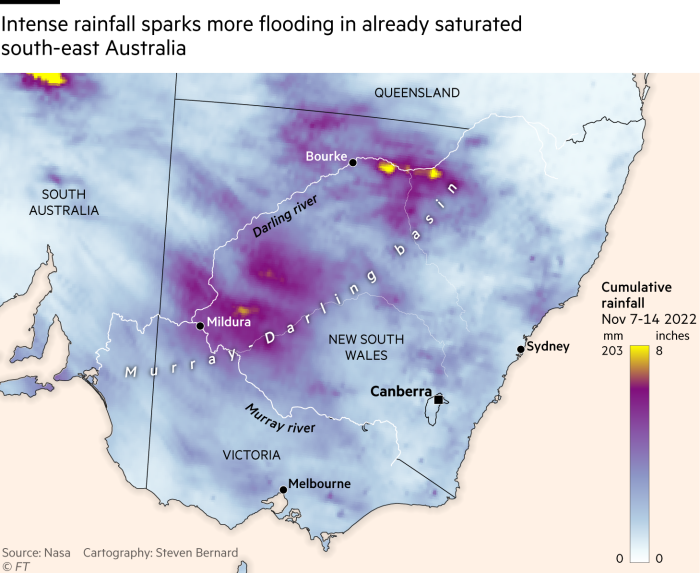

During La Niña events over the past two years, eastern Australia has experienced one of its most significant flood periods ever observed, said the country’s Bureau of Meteorology and national science agency CSIRO in a State of the Climate report this week.

The continent was now 1.47C hotter than in 1910, and sea levels around the coast were rising at an accelerating rate, said the report.

Heavy rainfall events had become more intense and the number of short-duration heavy rainfall events was expected to increase. Longer fire seasons were also expected in future.

Over the past two years, the same weather pattern has also contributed to severe drought in parts of Africa, including famine-struck Somalia.

During the El Niño phenomenon, which reverses these trends, surface winds across the Pacific weaken, ocean temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific are above average and there tends to be more than average rainfall over the central or eastern Pacific.

Scientists refer to a pattern where temperatures, winds and rainfall across the Pacific are at near-term averages as “Enso neutral”.

Global temperatures have already risen by at least 1.1C since pre-industrial times.

Michael McPhaden, a senior scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the US and one of the authors of the paper, said “stronger” El Niños would be detected before La Niñas because the particular amplifying feedback interactions between warming sea temperatures and weakening winds were “more vigorous”.

“A smaller warmer sea surface temperature will lead to a larger wind change, which will then lead to an even larger sea surface change,” said McPhaden.

He said droughts in places such as the western US were in part amplified by Enso effects.

Western US states have been gripped by a so-called “megadrought” for much of the year, driving water levels at the two largest reservoirs to record lows.

Earlier this year, US government climate scientists said more than half the country was enduring drought conditions. A separate study estimated that the drought affecting southwestern states was the worst to hit the region for 1,200 years after being exacerbated by human activity.

McPhaden said stronger versions of both La Niña and El Niño would likely amplify the existing effects of both weather patterns.

“The bigger the signal in the tropical Pacific, the bigger what we call teleconnections — the global reach of El Niño, and it will tend to be bigger for big events,” said McPhaden.

“So the expectation is that if we have stronger El Niños, we’re going to see these patterns that have repeated historically — from drought or flooding or wildfire or other extremes in the climate system — we should see those amplified in some sense.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here