This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Along with the rest of the FT, we’ve been watching the spectacular implosion of FTX, particularly how the crypto exchange muddied the waters of what counts as ethical business.

Its fallen founder Sam Bankman-Fried was an enthusiastic proponent of “effective altruism”, pledging to make vast amounts of money to help save the world by giving it away. The business flaunted its sustainability credentials with an advertising blitz introducing its new ESG adviser, the supermodel Gisele Bündchen. Now FTX’s governance catastrophe is adding to the backlash against ESG — as you can see from this Wall Street Journal editorial, claiming that Bankman-Fried has become “an ESG truth-teller” by revealing the whole agenda to be “a fraud”.

In its own way, Amundi, Europe’s largest asset manager, is also grappling with how to define what counts as ethical investing. It said this week it was planning to downgrade the majority of the €45bn it holds in the EU’s “greenest” fund category, Article 9, because of confusion over the rules for what such funds can include.

Today we look at one of the thorniest issues within the ethical investment debate: coal, the most carbon-intensive of the fossil fuels driving the climate crisis. As the wider market moves towards greener energy, who is still willing to run the risk of financing coal mines, and why? (Kenza Bryan)

Research shines a light on big investors’ coal exposure

Why are some institutional investors so heavily invested in coal miners? The usual response is they are simply tracking the global economy, in a world where coal remains a big source of power.

But new research compiled by academics at University College Dublin, and shared exclusively with Moral Money, suggests that some big institutional investors have much greater exposure to coal than they would if they simply mirrored the overall market.

The research examined the exposure of large institutional investors to bonds issued by 41 of the world’s biggest publicly listed coal miners by market capitalisation, identified by the Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI).

TPI is a project led by the UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment, which analyses the transition pathways of more than 400 of the world’s largest public companies in high-emitting sectors, including coal, oil and gas, aerospace and shipping.

How much coal bond exposure would an investor have if they merely tracked the market? As a rough proxy for this, the researchers used Vanguard, the world’s second-biggest asset manager and pioneer of passive tracker funds, which account for the large bulk of its $8tn under management.

The research found that Vanguard held $105bn in bonds issued by companies tracked by TPI — the largest figure of any global investor. Of this sum, 0.73 per cent was in coal bonds. Vanguard declined to comment.

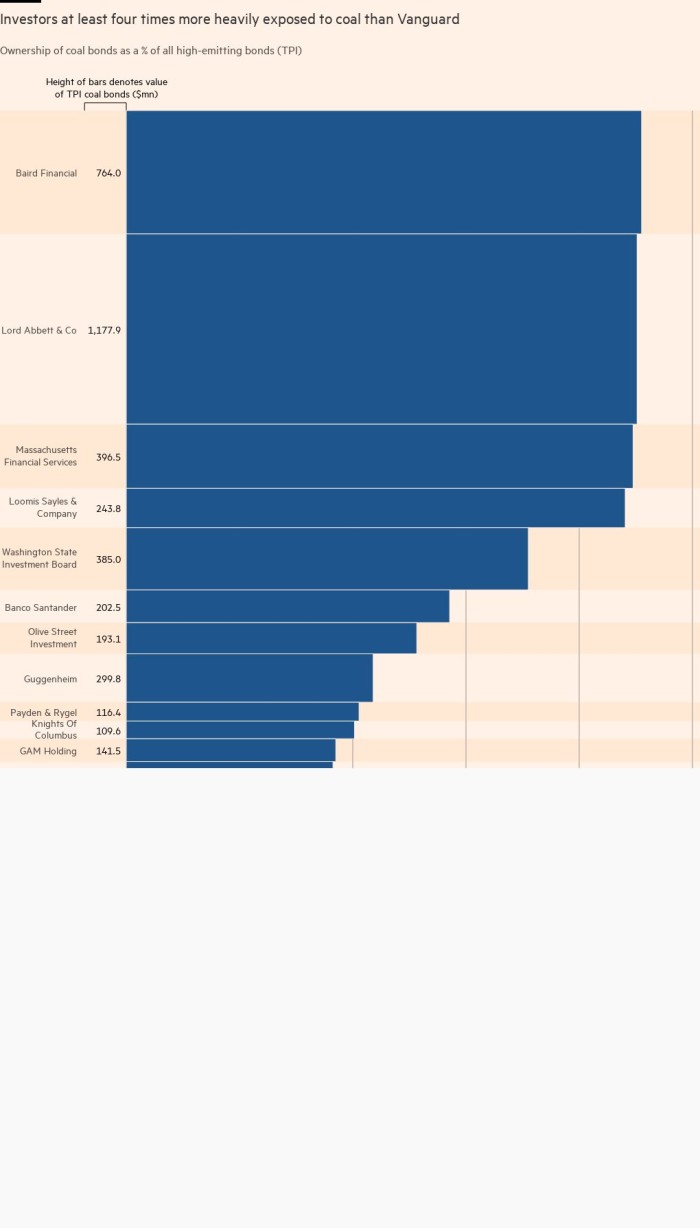

But that figure was far higher for many other big investors. For 20 of them, it was above 3 per cent, meaning their relative exposure to coal bonds was more than four times Vanguard’s, and in some cases more than 10 times.

Among those 20 institutions were the asset management arms of banks including HSBC, UBS and Santander, with respective exposures, using the methodology explained above, of 3.1, 3.5 and 5.7 per cent.

These three banks have all pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2050 in their equity and fixed income portfolios as members of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative. Santander told us it was monitoring its portfolio exposure to coal to reach its goal of having no exposure to thermal coal mining worldwide by 2030. HSBC and UBS declined to comment.

The decision to own coal bonds is significant because coal companies with the biggest expansion plans now raise 2.5 times more capital through the bond markets than through traditional bank loans, according to the Sunrise Project non-profit network.

“These managers are making actively dirty bets across their entire portfolios and putting more money in coal than the benchmark [Vanguard],” said Andreas Hoepner, one of the researchers at UCD. “They are financing the wrong thing, in very large proportions.”

The International Energy Agency estimates coal consumption will peak in 2023, but the high number of coal projects under way tells a different story. Coal production capacity has risen in recent years, and about 1,000 new coal-fired power plants are in the pipeline, mainly in Asia, according to non-profit group Reclaim Finance. These could remain in operation until well after 2060, it said.

The average maturity of coal-related bonds identified in the UCD data was after 2030.

The highest coal bond exposures of all in the study were at four independent US investment groups: Baird Financial, Lord Abbett, MFS Investment, and Loomis Sayles, with relative figures (using the methodology outlined above) ranging from 9.1 to 8.8 per cent.

New-Jersey based US investment manager Lord Abbett told me it had a “constructive view of coal”. It does not employ industry or sector level exclusions in its portfolio, and its exposures are the result of “individual, bottom-up security selection”.

Boston-based MFS said it believed in “the power of active ownership”, which allows for “ongoing, nuanced dialogue providing an in-depth understanding” of the companies it invests in.

Other interesting names on the list were the Washington State Investment Board and the Knights of Columbus — a male-only Boston-based Catholic fraternal organisation that offers funds “specifically designed for Catholic investors”. The WSIB said the coal-mining bonds identified represented just 0.6% of its fixed-income assets. Knights of Columbus declined to comment. Baird Financial and Loomis Sayles did not respond to a request for comment.

Stephanie Maier, head of sustainable and impact investing at the Swiss asset manager GAM — which ranks 12th in UCD’s coal bond top 20 — called for governments to build carbon pricing models that will accelerate the flow of capital towards cleaner energy.

“The point is this is not something to look at in isolation: signals from government policy are key,” Maier told me.

GAM’s exposure to coal companies included in the analysis is through two large companies for which thermal coal represents a small proportion of revenues, and which have transition plans in place, she said. GAM’s exposure as highlighted by the data also includes assets outside its direct investment management business.

“If there’s a very small exposure and the company has committed to transition away from coal, having engaged investors can drive positive outcomes”, she said.

But Maier hinted that GAM could yet revise its position on coal bonds. “We recognise that as shareholders and as bondholders we have different leverage points for engagement. Considering whether we would participate in future bond issuances is one of those leverage points,” she said.

Asset managers with much higher proportional exposure to coal than the “behemoths” of the passive world should at the very least be explaining which of their funds include coal, said Ulf Erlandsson, founder of the Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute research group. This would help “start the discussion” with retail investors about whether their cash helps back the coal industry, he argued. (Kenza Bryan)

Smart read

Saudi Arabia was blamed last week for what many said was a soft stance on fossil fuels at COP27. But the country has been talking a big game on renewable energy, as the FT’s Middle East Editor Andrew England and Saudi correspondent Samer Al-Atrush report in this Big Read.