Thirty years ago Cornwall resident and space buff Malcolm Butterworth blagged his way past Florida state police to watch the US Space Shuttle Columbia lift off from Cape Canaveral.

Today, as Virgin Orbit prepares to launch the first satellite from British soil at Spaceport Cornwall in Newquay on the country’s southwestern tip, Butterworth is again determined to do whatever it takes to be present. “I never thought I would see rockets launching from Cornwall,” he said with a shake of his head.

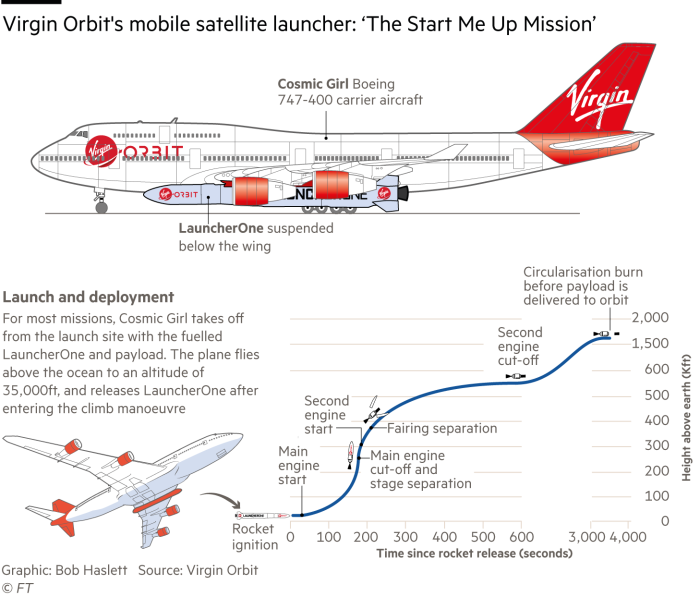

Unfortunately, there will not be much to see. Unlike traditional launchers, which rise in a cloud of steam from a launch pad, Virgin Orbit’s converted 747 aircraft, Cosmic Girl, will simply take off from the runway with a rocket tucked under its left wing.

The rocket will be released 35,000 feet above the ocean to the west of Britain to place the satellites into low earth orbit. But assuming the final licence associated with launch comes through this month, and the weather holds, it will still be a historic moment — the first satellite to be launched not just from Britain but western Europe.

“A lot of people said we couldn’t do it,” said Cornwall county councillor Louis Gardner on a visit to the spaceport this month. “But here we are.”

There is a great deal riding on the mission. For Cornwall Council, which has stumped up £5.6mn to deliver the £20mn project, it is a bold bet that the remote and rural county can attract high tech industry to spur economic development.

For Virgin Orbit, this will be the first mission outside its home base in California’s Mojave desert. Success will help prove that its horizontal launch system can be delivered anywhere in the world with a suitable runway.

And finally for the UK government, which funded £7.4mn of the cost, the mission fulfils its promise to launch a satellite from Britain this year. It also bolsters the country’s ambitions to be at the forefront of a new commercial space age in which services such as high speed broadband and climate monitoring will be delivered from space.

“We really want to be first [to launch from Europe],” said Ian Annett, deputy chief executive of the UK Space Agency. “We want to become the leading European supplier of launch.”

Achieving that goal will not be easy. The UK has approved the development of seven spaceports, offering both vertical and horizontal launch, roughly as many as China. It has also provided grants to galvanise the projects but expects them to be commercial operations.

These spaceports will enter a fiercely competitive market. Consultancy BryceTech estimates that more than 50 spaceports capable of orbital launch are operating or under development worldwide. For many countries, having a domestic spaceport is a question of national sovereignty, given the growing importance of space to security. But it is also about snaring economic benefit.

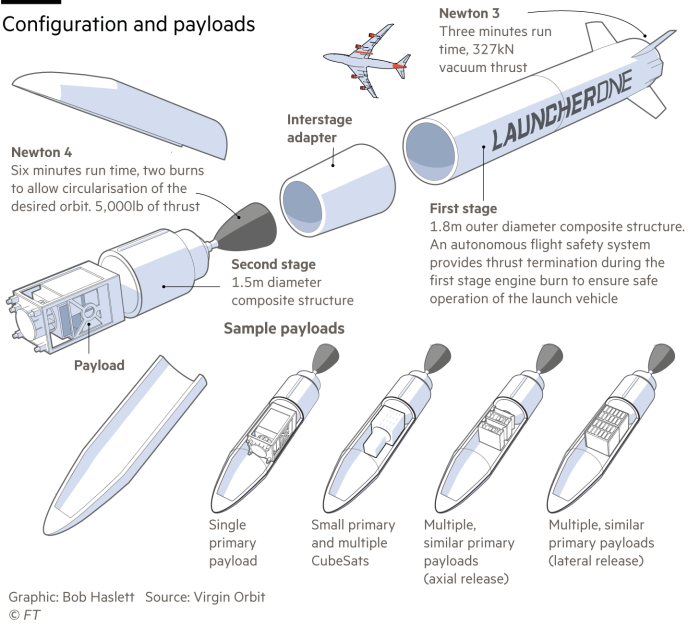

Space analysts Euroconsult estimate that, between 2022 and 2031, 18,500 satellites weighing less than 500kg will be launched into low earth orbit. But more than 80 per cent of these will be part of larger constellations such as Twitter owner Elon Musk’s Starlink, billionaire Jeff Bezos’s proposed Project Kuiper or China’s GuoWang, and they may fly from their own spaceports.

Many others may also choose to ride-share on bigger rockets, such as SpaceX’s Falcon, which can offer lower prices than many small launchers. Yet that could mean a long wait for a ride that may not place satellites in their precise orbit, according to some potential customers.

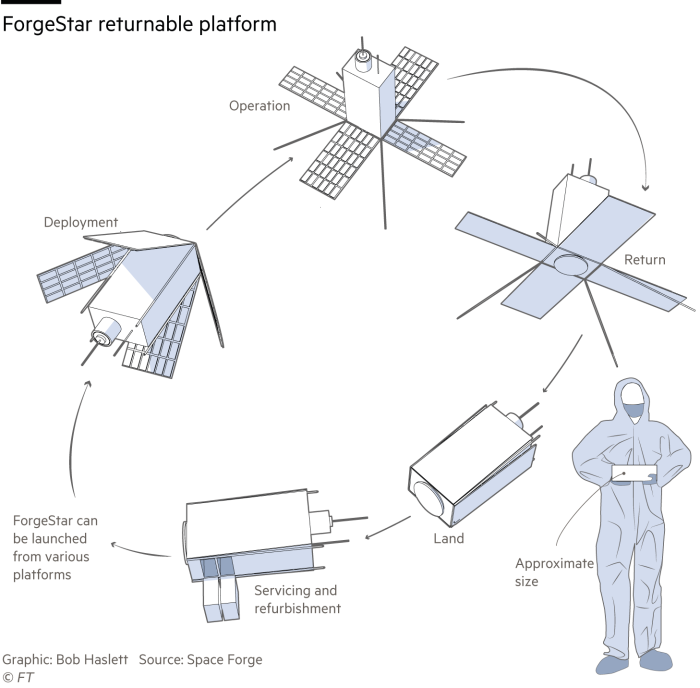

Timing is important to space manufacturing start-up SpaceForge, which is flying a test satellite from Cornwall. “The biggest worry is having a satellite in a clean room not doing anything,” said co-founder Andrew Bacon. “While satellites are on the ground, we are not learning.”

In 2018, a government-commissioned study on the addressable market for UK spaceports quantified the opportunity at $5.5bn. But not only will UK launch sites be bidding against each other for that business, others overseas will too.

“They will all compete with each other and in the end no one will have much,” said Alexandre Najjar of Euroconsult. “We already see spaceports that are nearly unoccupied, not living up to promises, especially in the US.”

Spaceport Cornwall has already had to revise downwards its forecast for expected launches from eight to two a year.

“The original figure was from 2018,” said Melissa Thorpe, head of Spaceport Cornwall. “There was a lot of chat about a huge market place . . . Then the pandemic hit. It became more pragmatic to think about what we could do in the next five years, looking at Virgin’s plans and what we could do.”

For some rocket companies, such as California-based Rocket Lab and the UK’s Orbex, it makes more sense to control their own launch sites. Peter Beck, founder of Rocket Lab, which owns three launch sites, said that without government subsidies or public contracts to guarantee business, life could be tough for independent spaceports.

“What the UK is doing, trying to grow the space industry, is fantastic,” he said. “But for our launch pad to be successful we need a certain cadence of launch. If you are launching infrequently, it’s not viable and that is why governments typically own launch ranges.”

Orbex has taken a 50-year lease on the proposed Sutherland spaceport in northern Scotland, where it plans vertical launch services. Chris Larmour, Orbex chief executive, said having control of the launch schedule and cost would be a “key driver of competitiveness”, adding that diversification was essential for spaceports without a dedicated, permanent launch partner.

In the Shetland Islands, for example, the SaxaVord spaceport will offer a ground station network for customers using its vertical launch service. Nik Smith, UK and Europe director at defence contractor Lockheed Martin, a partner on the project, said this had helped bolster the business case. The launch market “will be price sensitive, there’s no doubt about that”, he said.

For Spaceport Cornwall’s Thorpe, even if Virgin’s mission goes off without a hitch, it is only the start of the battle for long-term viability. The spaceport’s first launch has been hugely supported by the government. The LauncherOne rocket, for example, was flown over from California by an RAF aircraft. Not all launches are likely to have that level of backing.

Moreover, the very principle of Virgin Orbit’s system is that it is mobile, flying in with its own teams and equipment, launching the satellites and then moving on. There is no guarantee that Virgin will launch its European customers from Cornwall, although it is aiming for two launches next year and has so far invested £2.5mn in the project.

“After the first launch there will be conversations about the future of the spaceport,” said Thorpe. It wants to draw other operators and has signed a memorandum of understanding with US spaceplane developer Sierra Nevada.

Nevertheless, an ecosystem around launch is already developing. Companies such as Gravitilab, a microgravity testing start-up, and Expleo, a French engineering services provider, have been attracted by the possibility of doing business with spaceport customers.

The EU-funded Centre for Space Technologies, which includes collaboration and R&D facilities, has been filled five years earlier than expected.

“We are supposed to have an office in there and I don’t know if we do any more,” said Thorpe, laughing. “That facility wasn’t launch critical at all. But now we have it, we have a much more diverse offer. If a launch doesn’t happen one year, we still have an amazing business case.”