A B.C. judge has found a Chilliwack pastor “liable” for holding a worship service in breach of the province’s old COVID-19 orders — but a conviction for a $2,300 ticket won’t be entered until the court has considered a constitutional challenge.

In a decision with implications for a number of similar cases, Judge Andrea Ormiston found that while Free Reformed Church pastor John Koopman may not have organized the Dec. 6, 2020 event, he could be considered a “host” of the service, which contravened a public health order.

Despite the guilty finding, Ormiston held off entering a conviction last week — pending a challenge to the legislation that made the gathering illegal.

A spokesperson for the organization backing Koopman and other church leaders ticketed during the mandate says the ruling is part of a multitude of proceedings that continue to clutter the courts long after the order was dropped.

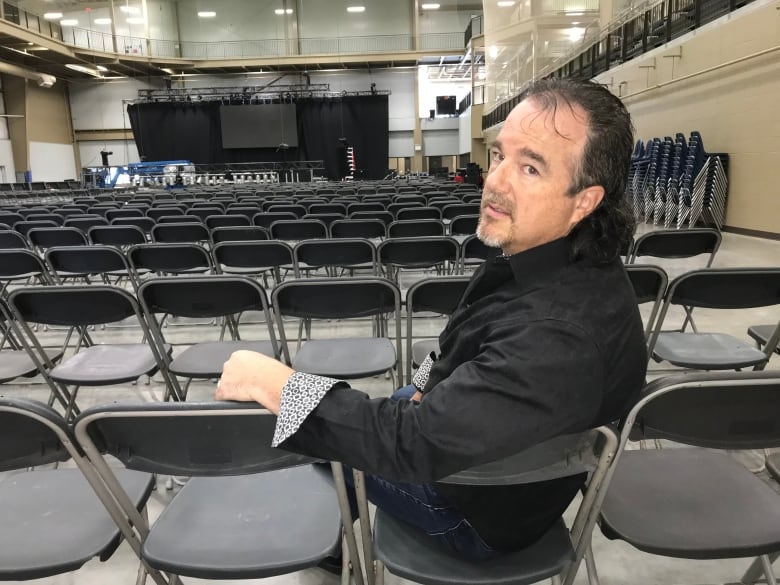

“It doesn’t leave a good taste in citizens’ mouths when they have gone through the legal processes and seen years of public resources expended against them for choices that had nothing to do with causing any additional health risk,” said Marty Moore, a lawyer with the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms.

‘A divine call that cannot be ignored’

While the Crown dropped two dozen COVID-19 violation tickets against Koopman and two other pastors last spring, Moore said more than a dozen remain and are currently being contested in provincial court.

The worship service at the heart of the case was held two days after Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry issued an order prohibiting people from organizing or hosting a long list of events, including in-person worship services.

According to Ormiston’s ruling, an RCMP officer “believed that a worship service was going to be held at the church that morning based on information from the church’s public website.”

The officer was prevented from going inside, but saw others being admitted. He later downloaded a video of Koopman’s service.

“During the sermon, pastor Koopman directly addresses the controversy of gathering in person to worship at that time,” the judge wrote. “As he said then, and as he explained in his testimony during this trial, coming together to serve God is a compulsion — a divine call that cannot be ignored or superseded by laws of the state.”

Ormiston’s ruling largely deals with the question of whether Koopman could be considered an organizer or a host.

The pastor successfully argued he was not an organizer, because his role is “intentionally removed from the administrative work of operating a church.”

But the judge found his role consistent with being a “host” who in “some way provides for the comfort and well-being of their guests even if they do not involve themselves with making the necessary arrangements.”

Moore said the distinction means Koopman will face a $2,300 fine as opposed to $230 for someone who simply attended — depending on the next step in the legal process.

Challenges at all 3 levels of court

Challenges to the legislation that enabled Henry to issue her mandates are now before all three levels of B.C. courts.

In addition to Koopman’s challenge in provincial court, the Court of Appeal is reconsidering a B.C. Supreme Court ruling that found while the top doctor’s orders may have infringed on religious freedoms, she was justified in issuing them.

Meanwhile, Moore said his group is asking a B.C. Supreme Court judge for a review of a September provincial court decision in which a Kelowna pastor lost his bid to mount a similar challenge to the one likely to be made in the Koopman case.

In that decision, Judge Clarke Burnett found Art Lucier was trying to make an “impermissible collateral attack” on the public health legislation because the law sets out a specific route for people who object to an order.

Lucier argued that this reconsideration process was “flawed and insufficient.” The judge agreed that it may not have been “robust” but said the right to appeal clearly existed — as did the right to a judicial review after that.

“The intention of the legislature was that only those individuals with the appropriate training and qualifications should be tasked with ascertaining the merits of any reconsideration,” Burnett wrote.

“To have another body do so may well undermine the primary objective of the legislation, being the protection of the public from health hazards.”

‘A reasonable and proportionate balance’

Koopman’s next court date is Dec. 21.

Moore says the legal proceedings are timely in light of considerations about the need for mask mandates to combat the spread of new strains of COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses.

“If we choose to engage the legal resources of our communities — policing, prosecution and judges — with the use of mandates, we can expect to have much less of those resources available to meet the other more pressing needs of our community,” Moore said.

“I think that is something within the public interest to be considered.”

In all cases, the province has argued that orders infringing the rights of Canadians were necessary to control the spread of a deadly virus that prompted a state of emergency.

In the decision now before the appeal court, B.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Christopher Hinkson echoed that sentiment.

“”Although the impacts of the … orders on the religious petitioners’ rights are significant, the benefits to the objectives of the orders are even more so,” Hinkson wrote.

“In my view, the orders represent a reasonable and proportionate balance.”