China’s doctors have a blunt message for Xi Jinping: the country’s healthcare system is not prepared to deal with a huge nationwide coronavirus outbreak that will inevitably follow any easing of strict measures to contain Covid-19.

The warning for China’s leader was delivered by a dozen health professionals — including frontline doctors and nurses and local government health officials — interviewed by the Financial Times this month, and echoed by international experts.

“The medical system will probably be paralysed when faced with mass cases,” said one doctor in a public hospital in Wuhan, central China, where the pandemic started nearly three years ago.

The warning also serves as a reality check for many in China and around the world hoping that Xi will end his hallmark zero-Covid policy. Experts said the policy meant China had failed to prioritise building robust defences for a mass outbreak, instead focusing its resources on containment.

At the heart of the problem that Beijing has created for itself is what many see as an inevitable “exit wave”, a rapid surge in infections as the country unwinds its heavy-handed pandemic restrictions.

That wave threatens to overwhelm the country’s healthcare services unless Xi and his top lieutenants make radical changes to the zero-Covid policy in preparation.

“The big threat in an exit wave is just the sheer number of cases in a short space of time,” said Ben Cowling, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Hong Kong. “I would be reluctant to say there is a scenario in which an exit wave doesn’t cause problems for the healthcare system. That is difficult to imagine.”

China’s official case counts are at their highest in six months, including a record number of infections in the capital Beijing and the southern manufacturing hub of Guangzhou.

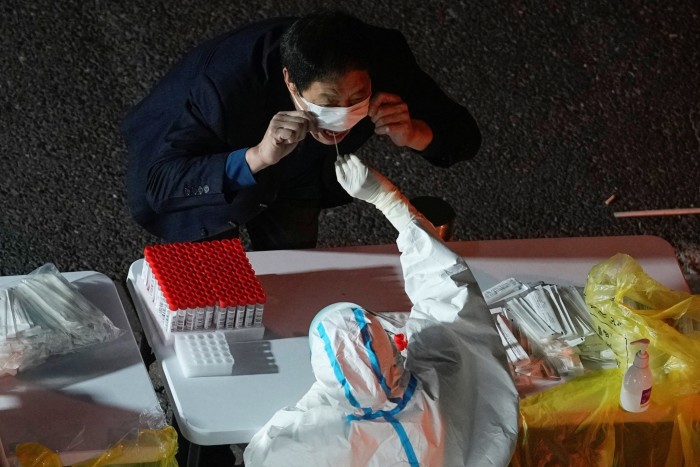

The zero-Covid strategy involves lockdowns — of buildings, suburbs or entire cities — as well as mass testing, quarantines and electronic contact tracing. While successful in suppressing outbreaks, the policy has exacerbated problems in China’s healthcare system and left a large chunk of the population deeply fearful of the virus.

China’s elderly have resisted taking a vaccine to prevent it. Only 40 per cent of those over 80 have had three shots of a domestically made vaccine, the dosage required to gain high levels of protection against the Omicron variant.

Jin Dong-yan, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong, said Chinese hospitals could be overwhelmed by an influx of unvaccinated elderly patients if there was a mass outbreak, replicating a crisis in Hong Kong this year when hospitals and morgues ran out of space at the peak of an outbreak.

“A Hong Kong-style outbreak is avoidable if they increase elderly vaccination coverage and stockpile antivirals, both things Hong Kong failed to do going into the outbreak,” he said.

Still, over recent weeks, some equity market analysts and traders have reacted with excitement to perceived signs of Beijing pivoting to a “reopening” plan — a change of course that they hope will reboot confidence in the world’s biggest consumer market and ease disruptions that have sporadically roiled global supply chains. Optimism increased last week after Beijing eased quarantine requirements for close contacts and international travellers.

According to frontline staff, nearly three years into the pandemic, China’s healthcare system is far more strained than at the start. Scarce funding, staff and medical resources have been redirected towards pandemic controls instead of preparations to treat the most vulnerable.

“Over the past few years, the Chinese healthcare system has completely limped along, putting all its manpower, funding and support into Covid prevention and control,” said a health official in southern China’s Guangdong province. “This is unsustainable.”

These concerns, the official said, have been relayed to Beijing.

“Unfortunately, the central government has still not made any substantial adjustments in the general direction,” the official added.

A nurse in a remote city in the southern region of Guangxi said smaller hospitals “don’t have the manpower or the equipment” to handle a big influx of patients.

Localised lockdowns have also left frontline staff marooned, with other workers pulling extra shifts to make up for their stranded colleagues. A thick layer of coronavirus-focused bureaucracy has also slowed everything in an already cumbersome system.

“Most local officials and healthcare workers are very often at the mercy of rigid administrative orders, which is what makes the tragedy of patients not being able to get medical attention in time happen time and time again,” said another doctor in Wuhan.

During a lockdown in Shanghai in April, frontline medical personnel struggled to cope with the increased workload after many staff were redirected to conduct citywide testing.

“The medical system is not ready for a large-scale reopening,” said another doctor working in a county-level hospital in Inner Mongolia, northern China.

In preparation for larger outbreaks, China has ordered local governments to undertake a huge construction drive since early 2020 to build field hospitals to isolate and treat mild and asymptomatic Covid cases. It has also called for isolation facilities to house both close contacts and positive cases.

Karen Grépin, a health systems expert at the University of Hong Kong, said that despite the hospital building programme, human resources were “going to be as much, if not more, of an issue”.

“In the past, they have been able to move them about the country — one province helping another — but this won’t be the scenario if Covid takes off everywhere at the same time,” she said.

“And it is hard to treat Covid patients when you are also sick,” she added, noting that during Hong Kong’s deadly outbreak this year, the city relied on additional health workers from mainland China.

Experts said Xi’s administration would need to rely on prolonged enforcement of social distancing, including school closures and work from home measures, slowing any return to pre-pandemic normalcy.

China would also need to reserve hospital and isolation facilities only for severe cases and follow the rest of the world in allowing asymptomatic and mild cases to isolate at home, in order to substantially ease the burden on its healthcare system.

If pressure on hospitals is not relieved and there is reduced care availability, Hong Kong’s experience shows that Covid death rates will be much higher, Cowling warned.

“When we look at the data in terms of the risk of fatality for people infected in March in Hong Kong versus February, their risk of death in March was about double”, as healthcare facilities there became overwhelmed, he said.

Additional reporting by Wang Xueqiao and Thomas Hale in Shanghai