The collapse of Sam Bank-Friedman’s FTX empire this month has visibly damaged other crypto players. But it has also had another, less obvious, impact: on a network of Ukraine-linked technologists.

The philanthropic FTX Future Fund had recently been providing discreet support to entrepreneurs developing innovative military tools for Ukraine. These technologists are now, they tell me, scrambling to find alternative donors after the “painful” shock of the exchange’s downfall.

I hope they find some. But this latest crisis underscores a wider point: the nine-months-long war in Ukraine has unleashed some unorthodox grassroots innovation that investors and policymakers would do well to watch. Most notably, a global network of tech talent has emerged that is sympathetic to Ukraine’s cause; partly because the country hosted numerous information technology services for companies across the world before the war.

As Ukrainians use this network to scramble for ideas they can test, or “hack”, on the battlefield, this is sparking some “extraordinary innovation”, as Brad Smith, president of Microsoft recently noted. It is also quietly reshaping some elements of the business of war. In 20th-century America, breakthroughs in military tech tended to emerge either from gigantic companies such as Lockheed Martin or Raytheon, or from government-funded institutions like America’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa).

The latter produced innovations such as global positioning systems and drones, which were subsequently absorbed into civilian tech. However, today there is a surge in rapid grassroots improvisation among so-called “non-state actors”, including terrorists. One example is reports that Houthis are using 3D printers to manufacture drones in Yemen.

What is striking about Ukraine, however, is that thanks to the internet, decentralised networks are improvising on a large scale. Sometimes this involves tech giants. Google has offered support in both visible and less visible ways. (One example of the former is that it has sometimes switched off parts of its traffic locator maps to help assist the Ukrainian defence.) Microsoft has also provided cyber security support — although even Smith notes that it is the nimble response of the Ukrainians themselves which has been crucial in fending off Russian attacks.

Meanwhile Elon Musk’s SpaceX has supplied civilian Starlink internet terminals to enable Ukraine’s satellite communications. He subsequently got cold feet, suggesting he had never intended them for military use. But I am told the Ukrainian tech network is now feverishly testing alternative satellite systems to support soldiers on the front line.

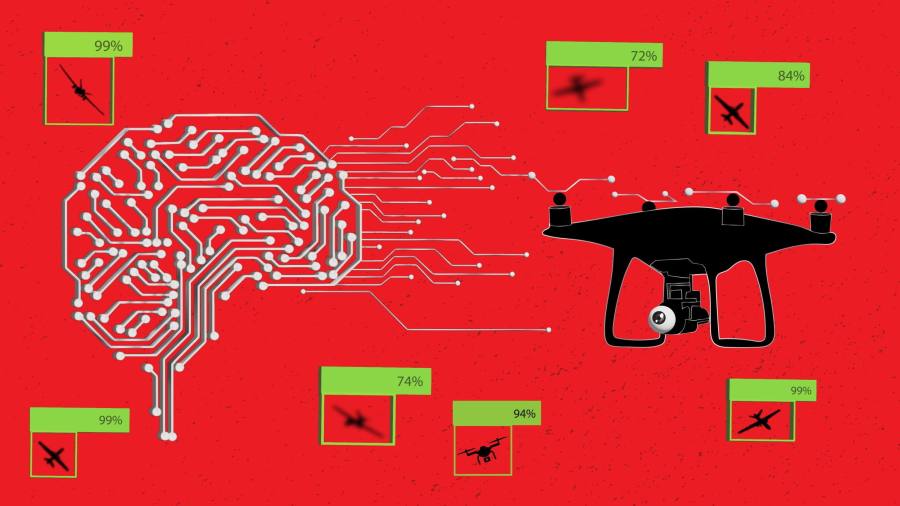

What is more noteworthy, however, is the role of young tech companies, mere toddlers on the innovation scene. Drones are a case in point: smaller companies such as America’s Dedrone, Turkey’s Baykar Technologies and Germany’s Quantum-Systems are the focus of rapid innovation. And consumer tech — which has become so powerful and cheap in recent years — is being commandeered by entrepreneurs in striking ways.

In the months after the Russian invasion, Ukrainian techies worked out how to put grenades on the type of cheap consumer drones sold online by companies such as DJI. They repurposed systems from companies like Dedrone to help combat Russia’s Orlan surveillance drones.

I am told some Ukrainian battalions are now trialing ways of countering the “swarms” of Iranian Shahed-136 drones that are currently being deployed by Russia. One idea is to use Bayraktar drones as quasi “sentries”, possibly with artificial intelligence capabilities (a move that would potentially take drone-on-drone warfare to new levels).

Meanwhile, seven maritime and nine aerial drones were recently dispatched, apparently by Ukraine, to attack Russian vessels in the strategic Black Sea port of Sevastopol. The bold move startled some military observers, who dubbed it “a glimpse into the future of naval warfare”. Kyiv has apparently developed naval drones that feature a propulsion system from a popular Canadian jet ski brand. This gives a new twist to the idea of dual-use tech.

The Ukrainians are certainly not alone in this repurposing: unexpected pieces of consumer tech from all over the world (even Israel) are also appearing in Iranian drones. But what is striking is Ukraine’s decentralised power structures — the grassroots entrepreneurs have a sense of agency that is rarely found in Russia, where vertical hierarchies dominate in military and civilian society alike. As commentators on Russian state TV have noted themselves, the culture of a country’s army invariably reflects its national identity.

Of course, such grassroots innovation has its limits: it cannot fix Ukraine’s desperate need for more powerful long-range missiles, or better air defence systems. It also needs reliable sources of funding, as the dance with FTX Future shows.

But this new wave of technology has already changed the trajectory of the war. And for those military strategists outside Ukraine, it will provide study materials for years to come. If and when the war ends, it may even offer a way for Kyiv to create a cutting-edge civilian tech sector. Here’s hoping.