It might be too early to assess the impact of the French Revolution LDI debacle. But that’s no reason why we shouldn’t be asking who is to blame.

The question of blame is important, partly because it keeps litigation lawyers in business. But mostly it’s because narrative is important. We all knew that the Great Financial Crisis was the fault of the banks; that knowledge set the cultural and regulatory agenda for the next decade.

The gilt crisis wasn’t quite of the same magnitude as the GFC, but it still managed to force a screeching U-turn in British fiscal policy and bring down the Truss administration, if not the Conservative government. Do we know yet whose fault it is?

Twitter polls are about as crazy-unscientific a train wreck as you can get from a polling perspective. But there didn’t seem a quicker way to take the temperature of FinTwit (or what’s left of it).

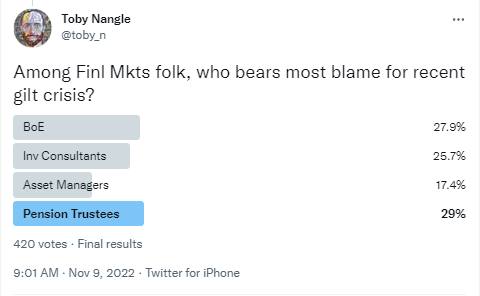

To start, when faced with the choice of blaming financial markets types or Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng, the financial markets types say they didn’t do it. In fairness, Truss and Kwarteng probably feel the same way about their own roles.

Who bears most blame for recent gilt crisis?

— Toby Nangle (@toby_n) November 9, 2022

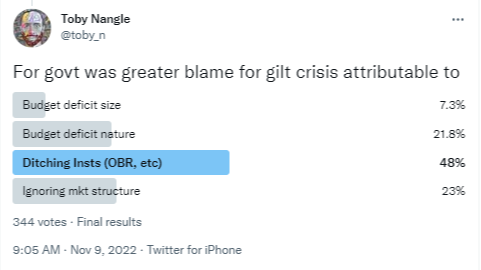

Digging a little deeper, an admittedly badly worded poll around what Kwarteng and Truss did wrong suggests FinTwit comes out firmly on the side of bad vibes rather than a massive budget deficit.

Ignorance of gilt market structure fragilities ahead of a highly questionable mini-budget looks like straight-up technical incompetence. But the folks with influence over what happens next — prime minister Rishi Sunak, along with chancellor Jeremy Hunt and the BoE — all reckon it was the size and nature of the budget deficit that was really to blame. So, in line with Duncan Weldon’s observations, FinTwit reckons the wrong lessons look like they’ve been learned by UK fiscal policymakers who are now set on a massive round of austerity.

Still, around a quarter of those who voted said financial market folks should be understood as mostly to blame. In this category, it’s the pension fund trustees who come out worst.

I can see the logic. Bad things happened, and these bad things very much involved pension funds. Pension fund trustees oversee and own the decisions around what pension funds do — including the decision to implement LDI, regardless as to whether this was done under advice or whether it was implemented in line with their expectations.

But there’s so much blame to go around, and so many actors. Privately, I’ve heard almost all sides make the case that blame belongs to pretty much every other party (with various regulators deserving special mention from almost everyone). There is also genuine uncertainty as to who will carry the can when Select Committee investigations get going.

The BoE meanwhile has presented blame analysis that implicates the Truss government, The Pensions Regulator, the FCA, asset managers and pension funds. It has also singled out pooled LDI funds that were designed and managed by asset management firms and chosen by pension fund trustees on the advice of investment consultants.

Assigning blame to one another in public is a different story. After all, defined benefit pension fund trustees are a huge client base, investment consultants serve as commercial gatekeepers for asset managers, and dissing your regulator tends not to be a great career choice. The only commercially prudent source of blame is really Kwarteng (even if many acknowledge that he was but the metaphorical kid playing with matches, who stumbled into the room they had crammed with fireworks, kindling and open drums of petrol.)

The House of Commons’ Works and Pensions Select Committee call for evidence into lessons learned closed on Tuesday. I’m expecting a precis of submissions from all parties to be:

But what if ignorance of gilt market structure was Kwarteng’s biggest sin? His not appreciating of the gilt market’s vulnerability to an LDI blow-up was a huge contributory factor to the crisis back in late September.

However, pension funds used the BoE’s intervention period to delever. The result is that the gilt market’s fragility has declined, perhaps meaningfully. Setting fiscal policy on the basis that September’s market fragilities remain in place — and will remain a permanent feature of the financial market landscape — risks compounding the technical incompetence charge sheet.

Narrative really does matter.