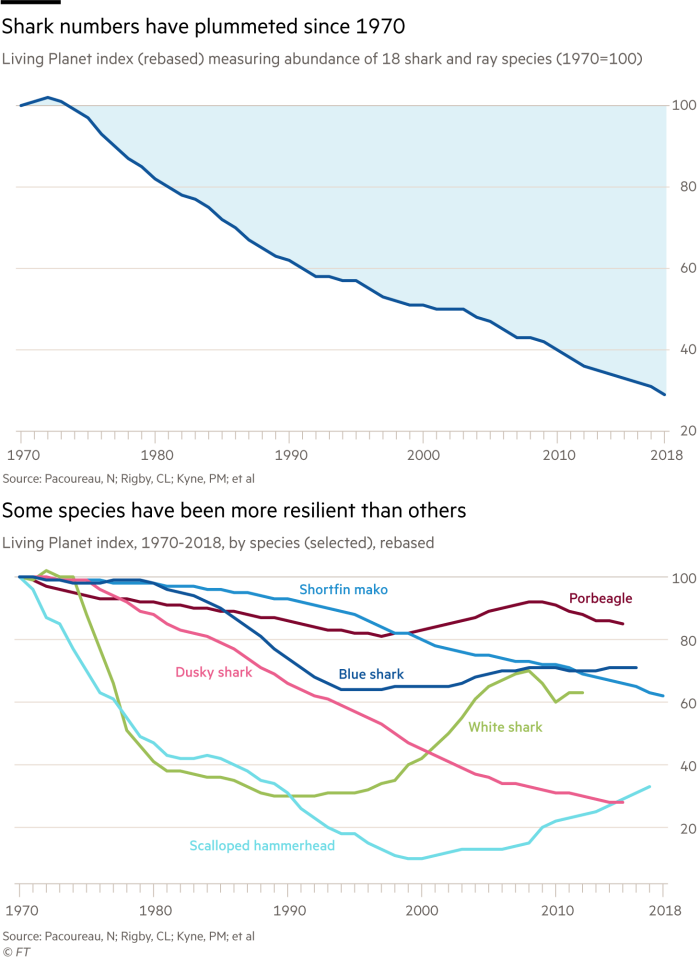

Sharks rarely eat humans. The multibillion-dollar trade in fins and meat means the real threat is the other way round. Though shark meat contains noxious chemicals, such as urea, overfishing has contributed to a 71 per cent decline in the numbers of 18 shark and ray species in the past half-century, according to research published in Nature.

If they knew, consumers might think twice about what they buy. Shark meat, tagged as “ocean fish” or “white fish”, finds its way into pet food, according to a paper published this year by researchers at the National University of Singapore, which relied on DNA sampling. Blue and silky sharks, graceful ocean wanderers that have become scarce, showed up most frequently.

The endangered position of sharks is on the agenda for this month’s triennial conference for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in Panama. As apex predators that take years to mature sexually and have few young, shark populations struggle to recover from overfishing.

This is not just about China’s passion for shark fin soup. Better technology enables fish processors to wash out shark meat toxins, contributing to their demise. Between 2012 and 2019, the value of trade in shark and ray meat at $2.6bn exceeded that of the fins by more than 70 per cent, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Spain is the largest exporter and a key importer as well.

Few consumers seek out shark meat — fins aside — suggesting that demand is not led by premium buyers.

Some species have suffered greater declines than others. Carnivorous dusky sharks have collapsed in numbers by 72 per cent since 1970. The giant and reef manta rays have almost disappeared in this millennium, according to the Nature paper.

Not all of this change occurs because of direct fishing of sharks. It may reflect loss of habitat and prey species too.

The decline in shark populations may mean that hunting them for meat makes less economic sense, albeit sharks often turn up as by-catch. The shark meat trade looks piddly compared with the figure of $160bn for all fish estimated by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, just for 2019.

Rare shark attacks grab headlines. But the casual extermination of apex species by humans to make pet food is just as troubling.

The Lex team is interested in hearing more from readers. Please tell us what you think of the shark meat trade in the comments section below.