European fast-food consumers demand long, straight chips, which means European potatoes need to be sizeable. But this summer, Europe’s weather had other ideas.

A punishing drought meant Dutch farmer Hendrik Jan ten Cate was forced to spray water from a local canal on his potatoes to prevent them shrinking. “Irrigation is very expensive. About 10 per cent of my costs was water this summer,” he says. “Farmers who could not irrigate lost half their harvest.”

Ten Cate’s other outlays were up 25 per cent, he says, because of the high price of gas. Fuel for tractors, fertilisers and pesticides all got more expensive.

He can see only one answer if Europeans still want to eat home-produced food: gene-edited crops, which are more resistant to drought and extreme heat.

“Climate change is coming faster than we are developing new crops,” he says. “We need new techniques. There is a big danger to food production in Europe.”

Gene editing is a form of genetic engineering where genes can be deleted or added from the same or similar species. It is distinct from genetic modification, which introduces DNA from foreign species.

Proponents argue that gene editing is the same as conventional plant breeding but simply accelerated, with greater accuracy. “If you introduce a foreign gene, it’s a GMO. If you just change the genetic letters within the organism, it’s conventional-like,” says Petra Jorasch of lobby group Euroseeds, which represents plant breeders. “This is also what you do with conventional breeding methods.”

That is not how it is currently seen in Europe. The European Court of Justice, the EU’s highest court, decided in 2018 that gene editing should come under GMO regulation, where regulators must give high priority to potential risks.

When GMO technology first arrived in Europe in the 2000s it met fierce opposition in a region that prides itself on the quality and provenance of its food. Products were labelled “frankenfoods” and trial fields were attacked by protesters. Regulators tightened rules so much that only one type of genetically modified wheat has ever been grown in the EU (although dozens of crops are now authorised for imports, mostly for animal feed).

Now, the mood on gene editing in Europe is shifting. In September, agriculture ministers from the 27 member states urged Brussels to speed up a re-examination of GMO regulation. The following month, the European Commission confirmed that it would issue a proposal to ease regulation for some gene-editing technologies in the second quarter of 2023.

The moves come during a year in which widespread drought cut harvests across Europe, with Spain losing half its olive crop. The war in Ukraine has reduced exports from a country dubbed the bread basket of Europe. The drought and conflict, combined with high energy costs, have driven up food prices and caused shortages in the developing world.

“The situation has changed. We have to be able to produce a sufficient supply of food. We need to take advantage of technology to adapt to climate change and maintain biodiversity,” says Pekka Pesonen, secretary-general of Copa-Cogeca, the EU farmers’ union.

But fears of “frankenfoods” run deep. Environmentalists and activists say agricultural companies have seized on climate change to foist untested technology on the public. Solving hunger is a seductive argument, they say, to win over politicians and sceptical populations without evidence to back it up.

“There is no reason to deregulate gene editing,” says Mute Schimpf, food campaigner at NGO Friends of the Earth Europe. “It is a new technology developed in the last 10 years. We don’t know how it might impact on nature, on agriculture and how the consumer interest will be affected.”

Yet Europe is now an outlier among large economies in treating gene-edited crops in the same way as GMOs, and some lawmakers are beginning to believe the risks are outweighed by the potential benefits for farmers, for the economy and for the environment.

“Plants obtained with new genomic techniques could help build a more resilient and sustainable agri-food system,” said Stella Kyriakides, European commissioner for health and food safety, when launching a consultation on her proposal this year. “This has been the guiding principle for EU food policy in the past and will always continue to be so.”

Pros and cons

Scientists have been crossbreeding species to create more resilient crops for decades.

For example, researchers have produced a strain of wheat that combines the high yield of one type with the solid stem of another, which helps it resist wind and rain.

Advocates say gene editing does much the same, more effectively. It could, for example, help develop wheat that provides nutrients to the soil, says Pesonen, reducing the need for fertiliser.

“They are fundamentally different to GMOs,” Pesonen says. “Imagine the improvement that we could get in the best-case scenario, both in terms of the nutrients or the protein content and the competitiveness.”

Hopes are also high for creating crops that can withstand the effects of the shifting climate. “If we could breed crops based on what we know on genetics to be more drought tolerant, more saline tolerant, more heat tolerant, and to produce more under certain conditions, that definitely could help us in terms of both food security as well as adaptation to climate change,” says Ismahane Elouafi, chief scientist at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Critics of the technology see this argument as a canard. They say the European Commission’s move is driven not by science, but by agribusiness lobbying, and that the current regulatory regime should be maintained. They are also concerned about the potential lack of transparency for consumers.

Christoph Then, of German NGO Testbiotech which warns on the risks of genetic engineering, says the intended and unintended changes caused by gene editing could go far beyond what can be expected from conventional breeding. “We think that there needs to be proper risk assessment. We think the current [regulatory] framework is appropriate,” he says.

Molecular geneticist Michael Antoniou at King’s College London warns that gene-editing technology is not as precise as claimed, is not the equivalent to breeding and is no different to genetic modification.

He fears unintended changes in the gene’s biochemistry and its composition. “You risk the possibility of creating new toxins and new allergens or adding to known toxins and allergens,” he says.

Martin Häusling, a German MEP who is the Green party’s spokesperson for agriculture, says there are other ways for farmers to tackle climate change, such as crop rotation, soil improvement techniques and naturally adapted seeds rather than turning to genetic engineering.

He and other opponents also charge that gene-edited products will further strengthen the grip of “Big Ag”, the large agricultural input companies, especially seed providers such as Bayer, Corteva and BASF.

Small-scale farmers will be left more dependent on external inputs, such as seeds, fertilisers and pesticides, he says. “They are therefore also more vulnerable in terms of bad years, and the climate challenges.”

However, supporters of the technology claim that gene-editing research and development is more accessible for small- and medium-sized players and university research labs than GMO development.

Technological advances have made gene editing relatively cheaper than that for GMOs, while some gene-editing technologies are provided on open platforms if they are for research purposes.

Companies and research labs based in countries that treat gene-edited products in the same way as conventionally bred products do not have to spend time and money dealing with the regulatory process.

Lower costs and reduced lead times have attracted scientists and entrepreneurs to launch start-ups, which have raised hundreds of millions of dollars from venture capital investors. Euroseeds says 90 per cent of its members are SMEs.

Not a silver bullet

Despite expectations that gene-edited crops could help mitigate the effects of climate change, the reality is they are still a pipe dream.

Only a handful of gene-edited products have been approved for sale, including a soyabean that produces oil with reduced saturated fat in the US, and a tomato with an amino acid that reduces blood pressure in Japan.

Even with gene editing, creating a crop which, for example, is drought resistant will take at least five years, according to scientists at the University of Calgary.

This is because there are multiple genes and various genetic structures that affect a plant’s tolerance to drought, and these need to be analysed, changed and tested incrementally.

Many advocates of the technology acknowledge that while genetic engineering speeds up research and offers greater accuracy in the changes, it is not a silver bullet.

While disease resistance is “quite easy to target in response to editing”, says Sarah Raffan, a researcher focusing on gene editing of wheat at the UK’s Rothamsted Research institution, drought resistance is a more “complex trait”. “This one gene might add a little bit of drought resistance under certain conditions, but you then need another gene for different things.”

There has been greater progress in gene editing to improve yields. Inari, a US agritech company set up in 2016, has been working on gene editing to increase yields on wheat, corn and soyabeans as well as reducing the necessary water and nitrogen fertiliser. Its chief executive Ponsi Trivisvavet, who oversaw a recent $124mn late-stage investment round, describes gene editing as a “super powerful technology”.

Inari is targeting yield increases of up to 20 per cent in corn, wheat and soyabeans, with input reduction targets of 40 per cent in water and nitrogen fertilise for corn. Trivisvavet says the start-up is almost there with its soyabean yield targets, noting: “All of this can’t be done with the [conventional] technology.”

Inari has research labs in the US and Belgium and Trivisvavet wants the EU to move faster on allowing gene editing. “If [the EU doesn’t] embrace this technology, it’s going to be super tricky to address [the effects of] climate change. We hope that the EU will actually join forces with the rest of the world,” she says.

Drought tolerance, yield increases, and improving yields with smaller amounts of inputs are complicated problems to solve, she notes. “You need to start now to actually address the problems that are escalating. If you start five years from now, it would be too late.”

The global outlook

EU policymakers who support bioengineering also fear falling behind the rest of the world in the technology race.

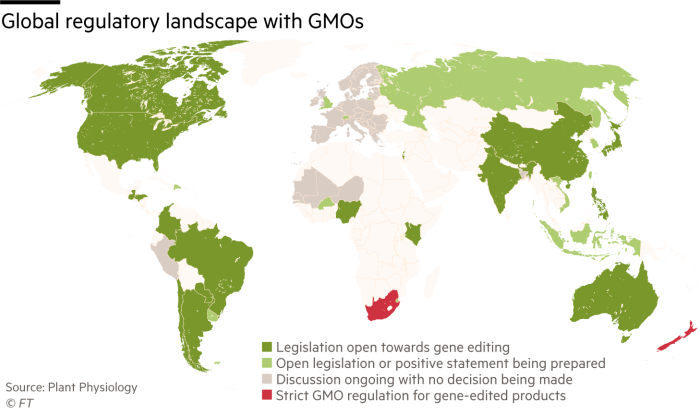

More than 15 countries have set rules that are open to gene editing in crops, including China, India, Argentina and Australia, according to Thorben Sprink and colleagues at Germany’s Julius Kühn Institute, a federal research centre for cultivated plants. Many countries, including the US, Canada, Brazil and Japan, do not differentiate gene editing from conventional breeding.

More governments have been clarifying their regulatory regimes around gene editing over the past few years. The UK is looking to ease its regulations since departure from the EU: new legislation that would allow gene-edited crops and animals to be developed and sold in England is to be debated in the House of Lords, the second chamber of parliament.

India earlier this year announced that certain gene-edited crops would be exempt from GMO rules. China, the global leader in crop gene-editing research with around 75 per cent of the world’s patents, introduced guidelines on commercialising products that, according to analysts, reduce the approval time from about six years down to one or two.

With the EU being a leading importer of agricultural products, including corn and soyabeans for animal feed, its policies on genetic engineering have a big impact on those of its trade partners.

That’s especially the case for developing countries that rely on income from the EU, says Elouafi at the FAO. “[With] countries from the global south, if there is a debate over gene editing [and whether it is] a GMO or not, they tend to not use it even for their research programmes. They are so afraid to lose the European market that they just stop using it.”

It also holds back R&D, scientists warn. “Plant breeders are hesitant to add breed varieties using genome editing if they’re not going to be able to sell it,” says Raffan.

Gene blues

The campaign to bring gene editing to Europe faces a steep obstacle: for the EU to rule that the technology is on a par with conventional breeding would require a qualified majority of member states in favour.

However Germany, the biggest member, has already said it would remain neutral, which counts as a “no” vote. Germany’s coalition government contains the Green party and they control the agriculture ministry. “I don’t think we currently have a majority of member states,” says Jorasch of Euroseeds.

Lawmakers may be influenced by a growing popular backlash against the technology. A recent public consultation by the European Commission received 70,000 responses with 98 per cent opposed to a policy change, as NGOs urged members of the public to write in, often providing canned responses for them to use.

Other surveys have found that consumers tend to have low awareness and knowledge of gene-edited food. A survey of more than 2,000 people by the UK government’s Food Standards Agency in July 2021 found that only 20 per cent of the respondents said they were fairly or very well informed on the subject.

After being given information on gene editing and GMO technologies, 39 per cent of the respondents said they thought gene-edited foods were fairly or very safe to eat, while 30 per cent thought they were fairly or very unsafe, while 31 per cent responded they did not know.

The European Food Safety Agency, which is responsible for risk assessments, in October published a report finding that gene-editing techniques were lower risk than GMOs, less likely to cause unintended mutations or interfere with traditional plants.

Advocates hope information like this will make sceptical lawmakers think twice, and consider what sustaining the ban on gene editing might mean for farmers. Brussels is still pushing ahead with plans to slash pesticide use in half by 2030, to reduce nitrogen pollution from farms — meaning less fertiliser — and to cut methane emissions from animals, measures likely to shrink the EU herd.

Farmers say they are running out of tools to maintain productivity. On his dried-out polder in the southern Netherlands, ten Cate, 45, wonders how long he can continue to grow his potatoes, onions, carrots and sugar beet.

“We have to innovate if we want to produce food in Europe,” he says. “Maybe we will become dependent on other countries if we do not adopt these new technologies.”