Almost 30 years ago, the Greek parliament voted to put on trial Constantine Mitsotakis, a former prime minister, for his alleged involvement in a scheme to wiretap political opponents and journalists. The case fizzled out after Pasok, the ruling socialist party, argued in a fit of generosity or self-interested political calculation that the charges should be dropped.

Now Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the ex-premier’s son and prime minister since 2019, is at the centre of a similar bugging scandal. Time will tell if it leads to legal proceedings. Meanwhile, the many unanswered questions about the affair are casting a cloud over Mitsotakis’s government.

This matters because Greece’s image has undergone a remarkable and in many ways justified transformation since the crisis years of the 2010s. It had once seemed possible that the country’s debt woes would result in a catastrophic default and exit from the eurozone, threatening Europe’s monetary union. Politics became polarised with the election in 2015 of Syriza, an insurgent party that formed the most radical leftist government in a European democracy since the second world war.

Slowly but surely, things changed for the better. Under the rule of a tamed Syriza, and then Mitsotakis’s New Democracy party, Greece satisfied the conditions of its creditors so successfully that the EU in August announced the end of its “enhanced surveillance” of Greek fiscal and economic policies.

Greece also became a valued partner in addressing regional problems. A settlement with the newly named North Macedonia laid to rest one of the Balkans’ most intractable diplomatic disputes. The EU heaps praise on Greece for its role in keeping out unwanted migrants. Athens has been a loyal Nato ally in supporting Ukraine after Russia’s invasion in February.

Regrettably, the bugging scandal suggests that not everything is hunky-dory in the politics and governance of post-crisis Greece. After taking office, Mitsotakis put the EYP, the national intelligence service, under his control and named Panagiotis Kontoleon, head of a private security company, to run it. Kontoleon resigned in August after the EYP admitted tapping the phone of Pasok leader Nikos Androulakis.

The next head to roll was that of Grigoris Dimitriadis, the prime minister’s general secretary, who had political oversight of the EYP. Dimitriadis happens to be Mitsotakis’s nephew.

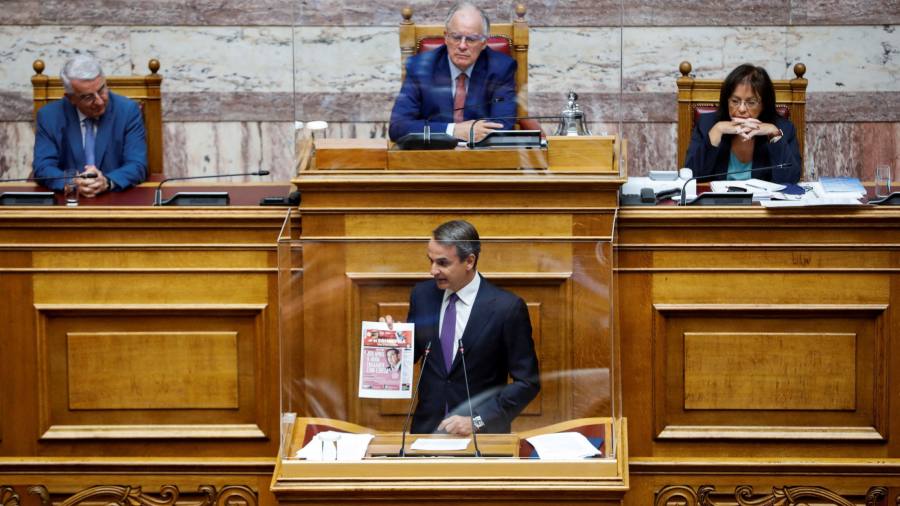

On Monday Mitsotakis repeated earlier denials that he had any involvement in the bugging. But the scandal refuses to die because the Androulakis affair is no isolated case. Someone — neither us nor the EYP, the government says indignantly — has been illegally using Israeli-made Predator spyware to hack the phones of other public figures, including investigative journalists.

A European parliament committee which looks into illegal use of spyware visited Athens last week in search of answers but left dissatisfied. Sophie in ’t Veld, a Dutch MEP, complained that the Greek authorities were not conducting “a vigorous search for culprits”.

It is not the only such mystery in Greece’s recent past. Around the 2004 Athens Olympics, the phones of about 100 people, including then premier Costas Karamanlis, were tapped for months. A decade later, it emerged that the bugging may have been part of a covert US operation aimed at preventing a terrorist attack during the event.

In the present scandal, Greek officials have dropped dark hints about hostile foreign involvement and invoked rules on state secrets to justify keeping matters under wraps. But the longer the government delays an explanation, the more it looks as if it has something to hide. Dragging its feet risks inflicting more harm on the reputation for steady, orderly government that Greece has painstakingly acquired.