This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Americans: go vote. Everyone else: think positive thoughts about the future of our republic. And email us: [email protected] and [email protected].

Big tech blues (part 2)

Yesterday I offered a sort of halfhearted mea culpa for my longstanding enthusiasm for the big tech stocks. I still think Alphabet, Apple and Microsoft are great companies with huge competitive advantages, but I concede that I have valued their growth a little too highly. Netflix does not share those companies’ competitive moats, and is less appealing. The tricky cases are Meta and Amazon, for opposite reasons. Meta is an immensely profitable business that is hardly growing at all and may be undervalued. Amazon is a fast-growing, not particularly profitable business that may be overvalued. Can we make sense of them?

Meta

Start by stating the obvious: Meta’s CEO and controlling shareholder, Mark Zuckerberg, is making an absolute mess of things. As we’ve already noted, structural changes and saturation have snuffed out growth in the company’s core advertising business (for now). That is not Zuckerberg’s fault, particularly. But he has piled an immense, concentrated, risky investment in a totally unproven idea, the metaverse, on top of the growth problem. Of course his bet could pay off, but the risk-return profile looks lousy. Facebook’s core business, growth or not, remains unbelievably profitable, and Zuckerberg needs to make it clear to shareholders that he is investing heavily in making sure that remains true, and is making several smaller bets on new products, rather than a single monstrous one. No one who invests in a $250bn company does so in order to play the tech lottery.

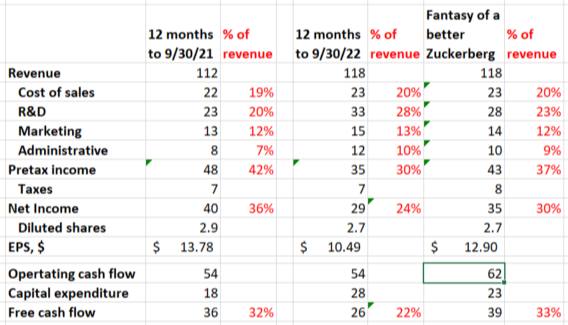

Here are three snapshots of Meta’s income statement, with a bit of cash flow data too. The first two are real: they are from the 12-month periods ending in September of 2021 and 2022. The third is a fantasy about what Meta’s financial could look like if Zuckerberg was a bit more cautious. The units are billions, except where otherwise noted. This will be impossible to read on a phone and I’m sorry:

The first two columns in black show you the ugly transformation Zuck has wrought. Year on year, revenue is up a little. But every expense line has risen a lot, with R&D expenses up a staggering $10bn. Capital expenditure is up $10bn too. Pre-tax margin has dropped a surreal 12 percentage points, to 30 per cent.

Meta needs to spend to solve its growth crisis. The question is how much, and how. The third column in black shows what Meta’s profit and free cash might look like if its spending increases had been half the size of the actual ones. Earnings per share would still be nearly $13, and free cash flow would still be rising. Combine that with some more measured CEO rhetoric, and a price/earnings multiple of 10 or so (just a shade higher than the current valuation) seems reasonable. That would render a $130 stock; today the price is $97.

If Zuck can cool it, my guess is that Meta shares have a lot of upside — so long as the company’s digital ad sales slowdown doesn’t get much worse. I have no idea about this. Of course this is all very crude (“Just spend less money and talk like a grown-up and the stock will go up!”) but some problems have crude solutions.

But what are the odds of Zuckerberg changing his approach? Because of Meta’s asinine shareholder structure, no one can force change on him. But perhaps watching his wealth decline, and his reputation dissolve, will motivate him. I have no idea about this, either.

Amazon

Amazon is trading at 81 times its earnings for the past 12 months. That’s a high multiple, and there are two reasons investors are willing to pay so much for so little profit. The first is that they assume the company will continue to grow very quickly; it is assumed it will “grow into” its multiple. The second is that investors assumed that Amazon could raise its prices and cut its expenses if it wanted to, but it prioritises growth instead. It could shift to profitability at will.

I think the second assumption is probably right, given the margins earned by the companies Amazon competes with, but I am losing confidence in the first, for philosophical reasons. I think what has happened to (just to pick two examples) Meta and Netflix should teach everyone that growth far into the future is not to be counted on. Best to assume that growth will mean revert suddenly, at some moment that is impossible to predict.

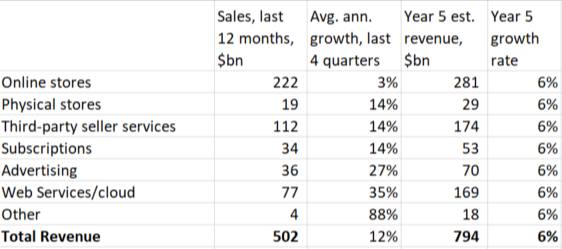

With this in mind, let’s think five years into Amazon’s future. Below is 12 month sales and average growth rates for each of its seven segments. What I have assumed is that over the next half-decade each segment’s growth shades evenly down to 6 per cent — a moderate sort of a number I picked out mostly arbitrarily. That renders a compound annual growth rate of about 10 per cent over the next five years (still pretty good!).

So, on this schematic picture, Amazon will be generating annual revenues of just under $800bn in late 2027, and growing at about 6 per cent a year. This picture is going to be way off, of course — too high or too low. This is an exercise in making non-crazy assumptions and seeing what they render.

The next step is to think about what margins 2027 Amazon will be earning, and what multiple investors will be willing to pay for the stock. Amazon’s operating margin has bounced around in the low-to-mid single digits for years. Let’s suppose they can push that to 10 per cent. That is not utterly implausible, as the retail businesses move from the growth to the harvesting phase, and the very high-margin cloud business becomes a larger slice of revenue. If Amazon then has an average US corporate tax rate (20 per cent) and the share count doesn’t grow too fast, it could be earning almost $6 a share in five years. (Guesswork? You bet.)

What will investors be willing to pay for Amazon in five years, when it is growing at 6 per cent on the top line? I don’t know. Let’s say they are willing to pay 22 times earnings, which is what they pay for Apple today (Apple is growing at 8 per cent). That would render a stock price of $128 in five years’ time, giving investors a thoroughly average return of a little over 7 per cent a year for the next five years.

All this tells us, of course, is that in the absence of very strong growth many years into the future, Amazon is not cheap. But there is another issue: what would the transition from Amazon as king-of-the-growth-stocks to Amazon as profitable-but-plodding look like? Apple shares have handled something like this transition smoothly, but Apple’s valuation never reached the dizzy heights of Amazon’s.

One good read

Difficult to accept but possibly true: “It was Donald Trump who closed the gap — in rhetoric, if not always in his eventual policymaking — between the Republican party and reality.”

Recommended newsletters for you

Cryptofinance — Scott Chipolina filters out the noise of the global cryptocurrency industry. Sign up here

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here