In October, during a tense meeting with then chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng at the UK Treasury’s office in the centre of London, the chief executives of Britain’s high street banks bemoaned the fact that Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan were using customer deposits to fund risky trading operations.

The UK’s ringfencing rules, imposed in 2019, allow banks to raise up to £25bn in retail deposits before they must be separated from their investment banking arms. That limit, the domestic banks told Kwarteng, puts them at a clear disadvantage in a fight with Wall Street insurgents hoovering up UK savings.

JPMorgan, who views the UK as a testing ground for low-cost digital banking, found the complaint ridiculous. A person close to the bank pointed out that they already had the largest consumer bank in America for gathering deposits. In the US, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1935, which prevented deposit-taking banks from dealing in securities, was fully repealed in 1999.

For Goldman, it hit closer to home as the Wall Street giant did enter the UK retail market in 2018 partly in search of a cheap way to fund investment banking. So far it has racked up £23bn in savings, staying studiously below the ringfencing limit while lobbying to have it scrapped or increased.

Now, the US banks, facing pressure from shareholders over the costs of their overseas operations, must continue to justify their ventures as recessions bite. While, for the UK banks, some of who are moving to aggressively compete for deposits which are getting ever more valuable as rates rise, the battle lines have been clearly drawn.

“It’s odd that incumbents are disadvantaged on home soil compared to international banks by the ringfencing rules. Those are deposits which we could use to support UK plc but are funding other activities,” said a senior executive at one of the UK’s big four banks.

When Goldman Sachs launched its app Marcus — established two years earlier and named after one of the bank’s founders, Marcus Goldman — in the UK, it was the first time in decades that a US investment banking giant had moved into Britain’s competitive personal finance market

Marcus started out as a savings product offering a chart-topping 1.5 per cent interest for a year, and has added on services including a cash ISA and fixed rate saver account. It has rapidly grown in the UK, amassing £23bn of savings.

“When they first arrived they built up a deposit book very quickly with an attractive rate at the time of around 1.5 per cent,” said John Cronin, analyst at investment bank Goodbody. “But since they got to around £20bn in size, I’ve heard little about them.”

Three years after Goldman, JPMorgan made its first foray into retail banking outside of the US with its app-based bank, Chase. It took a different approach to its rival, choosing to focus on building customer relationships with a current account with a year of 1 per cent cashback.

In March, it followed that with a linked savings account paying 1.5 per cent on savings of up to £250,000. At the time, Marcus paid between 0.7 and 0.6 per cent.

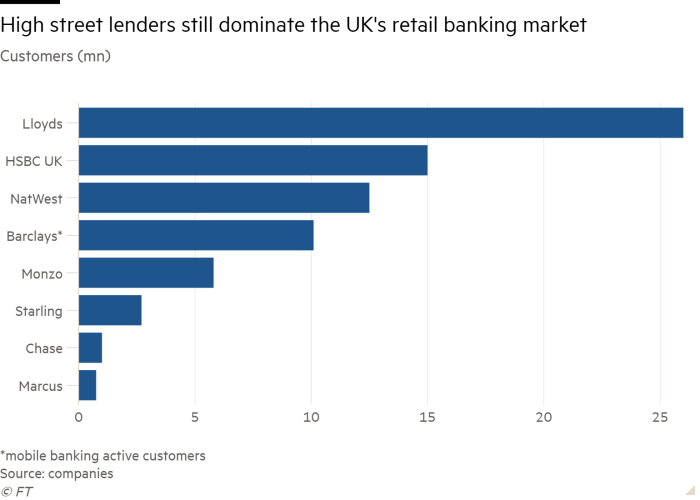

Its strategy has already attracted more than 1mn customers, surpassing Marcus’s 750,000 after just one year. It still lags behind on deposits, however, at £10bn.

“Chase had the smartest market entry,” said the chief executive of a challenger bank. “They launched this amazing rate . . . that helped grow their current accounts.”

Unlike the UK’s digital banks, such as Monzo and Starling, both Marcus and Chase have the backing of huge institutions with investment firepower and large balance sheets.

“Chase [in particular] has the balance sheet to make this work as a multiyear project,” said Cronin. “It’s very clear they’ve taken a very long term view. I think that’s the name I’d be a bit worried about if I was an incumbent.”

An expensive gamble

But the US banks’ strategies are under scrutiny. Goldman Sachs has already scaled back some of its plans, as economic conditions have darkened.

One aim had been for Marcus to branch out into wealth management to become the go-to app for personal finance. But Marcus UK’s chief executive Des McDaid said that since “UK consumers are under a lot of pressure at the moment . . . we may look at the timing of future product launches.” Previous plans for a stocks and shares Isa were shelved in 2020.

Both Marcus and Chase launched with the highest rates when the Bank of England’s base rate was just 0.75 per cent. But the rise in rates to 3 per cent has boosted the income of all banks, allowing them to pay back more to depositors. That has forced Chase and Marcus to increase their own offers to stay at the top of the charts.

According to Moneyfacts, Al Rayan Bank tops the best buy charts for easy access accounts with 2.81 per cent rate. Chase’s saver account rose to 2.1 per cent in October while Marcus increased its savings rate to 2.5 per cent, including a 0.25 per cent bonus for 12 months.

McDaid said that Marcus’s priority was to “continue offering competitive savings rates to [its] customers.” The bank has raised its rate nine times in 2022, almost as many times as it changed prices in the previous three years.

The two apps are also under scrutiny from shareholders over costs. Although Marcus UK is profitable, Goldman Sachs’ global consumer banking business is the group’s only loss making division, facing scrutiny from investors and internally. As part of a sweeping reorganisation, Marcus will fall under the bank’s combined asset and wealth division.

Chase is predicting losses totalling more than $1bn over the coming years and does not expect to break even until 2027.

Sanjiv Somani, UK chief executive of Chase, defended its costs. “I wouldn’t call it a price to be paid — it’s a strategic investment in a business which has huge potential,” he told the FT.

Others outside of the banks have also voiced doubts about the ambitious and expensive plans. “I’ve heard about this story for 25 years and haven’t seen any success,” said one senior figure at a large European bank.

An executive at a UK bank said that while they had seen some outflows of money to Chase, they expected it to be temporary. A similar trend had taken place when Marcus first launched but much of this cash had returned, they added.

“For the big banks, it’s something they are monitoring closely but not unduly concerned about,” said Neil Veitch, global investment director at SVM Asset Management. “They’ll be more concerned if they start to feel clients are paying their monthly salary into that type of account.”

UK launch pad

Despite the challenges, Chase at least is intent on expanding. Somani at Chase said it is aiming to further integrate its digital wealth management arm Nutmeg, which it bought last year for about £700mn, with its retail banking app.

Chase also plans to use the UK as a launch pad and Goldman might eventually follow suit. Last year, Chase acquired a minority stake in the Brazilian digital bank C6. Marcus had hoped to push into Germany as its first market in mainland Europe, although a person close to the bank said those plans are on hold.

But to push further afield requires success in the UK, where both are building themselves up into fully-fledged banks. Competitors remain sceptical they can take the next step.

“You can’t fake being young — they’re very long established investment banks with new retail bank arms,” said another challenger bank executive. “I’ll be personally surprised if they make much headway, but I’ve been surprised before.”