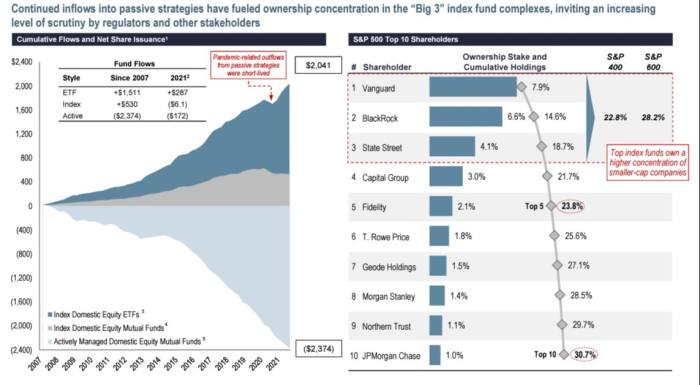

Of all the interesting, simplistic, or downright moronic arguments aimed against passive investing over the years, that the phenomenon would lead to an unhealthy concentration of corporate power always felt like one of the stronger ones.

You don’t have to be a believer in the “common ownership” theory (that large cross-industry shareholding might diminish a company’s competitive zeal) to feel a little uneasy at the idea of just a handful of asset managers exerting de facto control over swaths of the economy.

Both the right and left have been savaging big asset managers like BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — the Big Three of passive investing — either because of their perceived inaction or hyperactivity on a range of subjects.

Even Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, admitted before he passed away in 2019 that the emerging oligopoly of index fund giants that might in the foreseeable future control the majority of the US stock market would not “serve the national interest”. This week therefore feels like a bit of a small moment. A small-m moment, but a moment nonetheless. From the FT this morning:

BlackRock will allow retail investors to vote on proxy battles for the first time as it fends off criticism that its stance on environmental, social and governance issues is at odds with some of its shareholders.

The world’s largest asset manager plans a pilot with UK pooled funds to enable their investors to vote on contested proposals in 2023. Larry Fink, BlackRock’s chief executive, said technology is enabling a “revolution in shareholder democracy” that will “transform the relationship between asset owners and companies” as he announced the plans on Wednesday.

And from Bloomberg on Wednesday:

Vanguard Group is planning a trial to give retail clients more say over how their shares are voted at corporate meetings, as large money managers’ influence over hot-button issues faces mounting scrutiny.

Instead of making decisions exclusively on its own, Vanguard will give individual investors in several equity index funds more options about how their shares are voted, the Valley Forge, Pennsylvania-based company said Wednesday in a statement. It will begin testing the strategy early next year.

This follows Charles Schwab announcing a few weeks ago that it would pilot a new fund shareholder polling solution to get their input on various proxy issues. We wouldn’t be surprised to see similar announcements from the likes of Fidelity in the coming months.

So why is it not a Big-M moment? First of all, these are obviously just pilot schemes. But the biggest issue is the thorny reality that the vast majority of investors don’t actually want or care to vote.

Even big institutions have generally been fine with delegating all that pesky proxy work to their asset managers, maybe only occasionally weighing in on specific issues or major questions. Retail investors in mutual funds are largely oblivious.

Even in the era of ESG, where “asset owners” show more willing to get stuck in, the fact remains that the majority don’t really want to get involved in corporate governance, and certainly not the often-pesky details that proxy voting involves. And nor do most asset managers.

This is literally the reason why proxy advisory firms Glass-Lewis and ISS exist. Voting is considered an essential part of an asset manager’s fiduciary duty, so they sprung up to handle all the dull proxy work. Between them ISS and Glass-Lewis in practice command more votes than BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street combined.

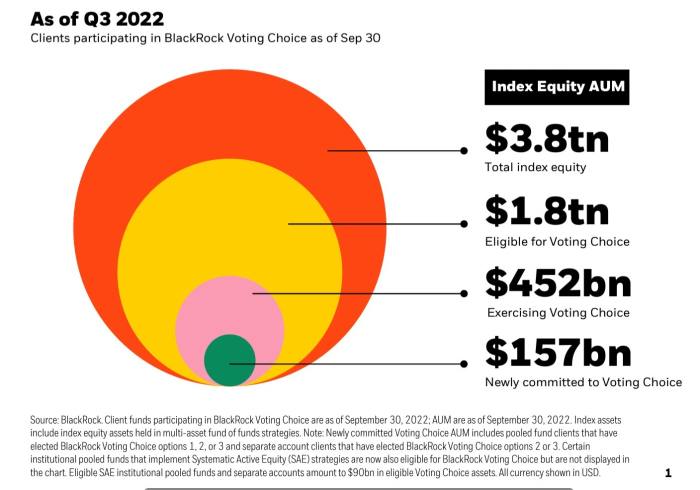

To see how muted interest in direct shareholder democracy is even among big asset owners, look at BlackRock’s “Voting Choice” programme for institutional investors. Of the $1.8tn of assets eligible, only $452bn have taken the opportunity so far (Update: the $157bn figure below is for clients that have signed up this year).

Retail interest is likely to be several orders of magnitude lower, and while institutional investor buy-in might increase over time, most ordinary investors are realistically never going to bother.

With that in mind, these pilot programmes look mostly like desperate attempts at deflecting the torrent of criticism heaped on the likes of BlackRock and Vanguard.

That all said, it’s still a genuinely interesting development.

Yes, many big investors are probably happy with letting their asset owners or the proxy advisers control their votes, and most retail investors will probably not even be aware of the possibility that they can vote in various companies’ AGMs. But some will.

Power attracts people like dung attracts flies, and there is unquestionably power attached to pooled corporate ownership. And as at least some of that power starts to dribble out of asset managers, someone will figure out a way to harness it.

Already there is an inchoate asset management lobbying industry, with various interested parties trying to convince the big money managers to come around to their views on a range of issues. But as voting power starts to migrate to individual investors, perhaps we will see a new breed of organisations that will ask us to cede our shareholder votes to them, based on our views on the environment, corporate compensation, human rights, evangelical values or drill-baby-drill.

Basically — and we’re very much in spitballing territory here — the emergence of corporate-political pseudo parties, built around pooling the corporate votes of individual investors according to their political and cultural preferences?

Further reading:

— Passive attack: the story of a Wall Street revolution. The explosive growth of index funds has changed markets. How far can they go? (FT)

— How passive are markets, actually? More than you think. Much more (FT)

— The power of twelve. The financial industry’s new emperors (FT)