This First Person column is written by Antonia Reed, a CBC producer in Toronto. This piece was written as part of the CBC’s Doc Mentorship Program. For more information about CBC’s First Person columns, please see the FAQ.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to learn Swedish.

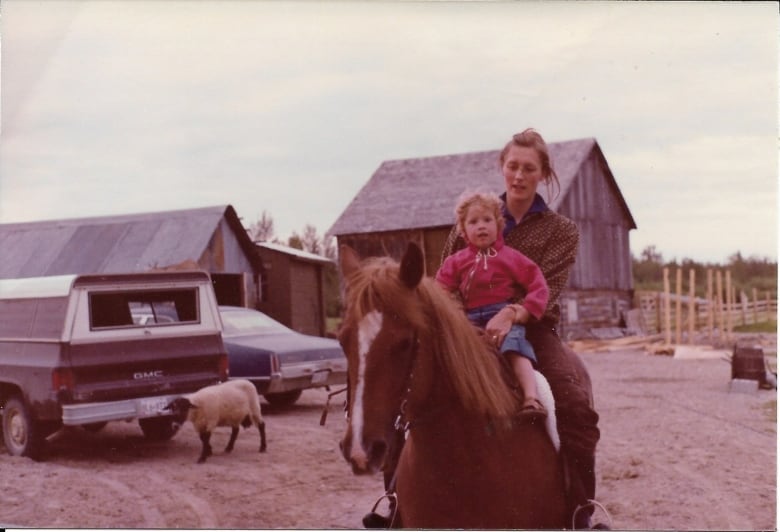

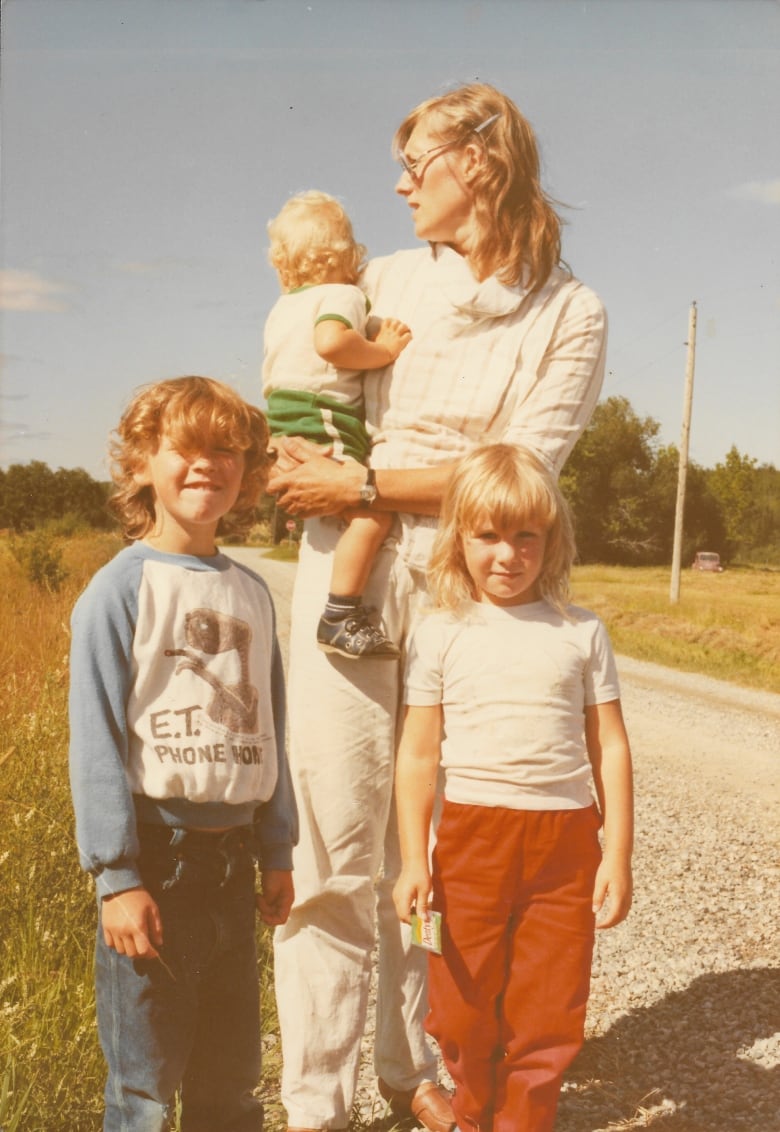

My mother started out with the best intentions of having bilingual children. She moved to Canada from Sweden in the 1970s where she met my dad and settled on a farm in northern Ontario. When I was a baby, she started out by speaking to me exclusively in Swedish and she would often tell me that my first words were in Swedish. But by the time my sister and brother came along, we were all strictly English-speaking kids.

My mother never put any pressure on us to learn Swedish and I didn’t put much effort into it while I was growing up. But in my late teens, I came to believe that if I didn’t learn the language eventually, it would be a major failure.

My desire to learn Swedish became acute after my mother died when she was 47 from breast cancer. I was 20, and along with grieving for the woman I loved most in the world, I was also left with the regret that I didn’t learn Swedish from her while she was alive.

But then a few months before my 40th birthday, I got a second chance.

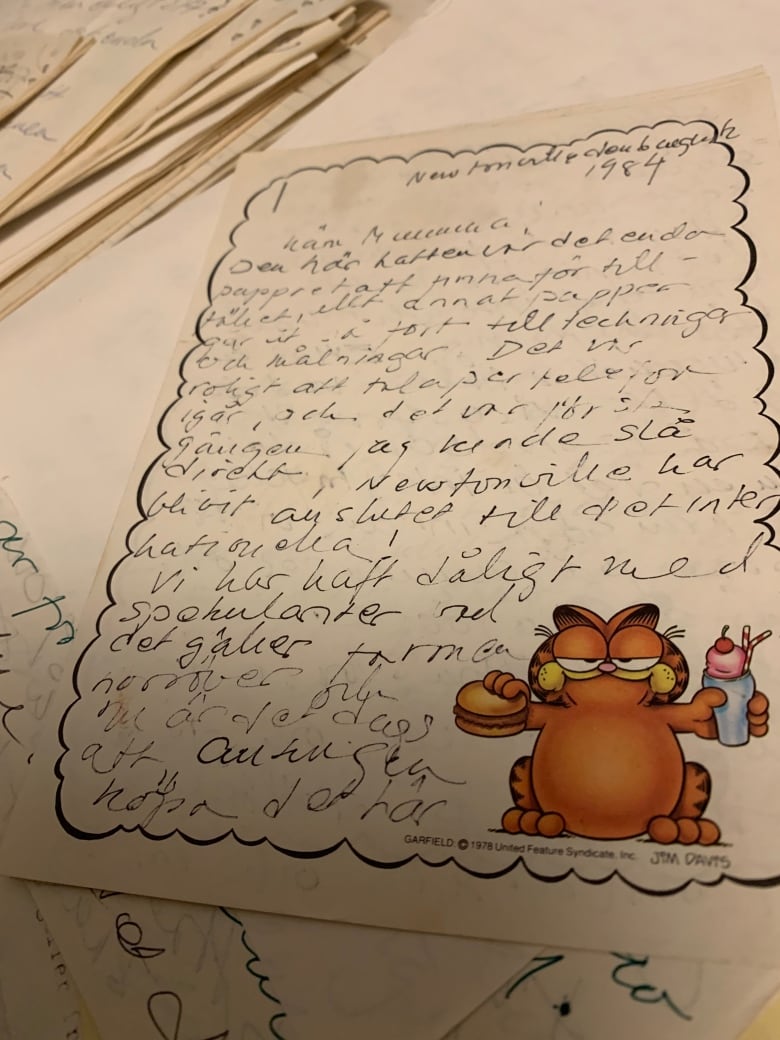

I got a Facebook message from my sister who was on a trip to Sweden. She discovered that our aunt Sophie, my mother’s eldest sister, had kept all the letters my mom had sent to our grandmother in Sweden throughout the 1980s and 1990s. There were storage boxes in her apartment filled with them. Turns out aunt Sophie sees herself as the family historian and never threw anything away.

I thought to myself, “This is it! I will get to speak to my mother again.”

I had to see them for myself, so I flew to Sweden and collected all the letters from my aunt. To my dismay, I quickly realized I couldn’t read them. The writing was a messy scrawl, and the fact that they were written in Swedish meant that I could barely decipher anything.

At the time, I had recently been diagnosed with major depressive disorder. I was torn between my home life and the office. I had two young kids who I felt I was neglecting by going into work every day. I was certainly not living up to the standard that my mother had set by putting her career on pause to stay home and raise us.

All I could think was that these letters might give me the motherly advice I needed — if only I could read them. I set myself the goal of becoming fluent enough in Swedish to understand them.

I had some basics I still remembered from growing up around my mom and her relatives, but now I actively decided to learn the language. I did Duolingo religiously, attended in-person Swedish lessons where I could find them and eventually found a Swedish teacher living in Italy who I met for a weekly language class over Skype.

One day, my partner asked me why I was spending so much time and money talking to strangers when I could just call up my relatives in Sweden and practise with them.

The truth was I was terrified.

When we travelled to Sweden during my childhood, my cousins would laugh at my attempts at speaking Swedish, and anyone else I encountered would immediately switch to English when speaking with me.

But I knew I would never be satisfied with my own progress unless I was able to speak to my family.

I called up my aunt Sophie and my cousin Helena in Stockholm and tried out a little of my Swedish on them. My aunt promised to help me translate the letters, and I promised to call her up again after months of intense Swedish practice. When I did, my aunt told me I was “gifted” in the language.

But there were still the letters, unread in my drawer at home in Toronto. With a burst of newfound confidence after my aunt’s praise, I decided to try reading my mom’s letters again after nearly seven years.

As I read, my understanding of the language and my mom’s life grew, and little details started to emerge: How my parents fixed fences around the farm, sheared sheep and planted gardens. When my sister learned to speak, me going to school; then later, when my brother — who was a handful as a baby — was plunked in front of the TV so my mom would have time to write.

I got into a rhythm reading her letters, not worrying so much about understanding every word.

I started to add details from the childhood I remembered: harsh weather with winter temperatures sometimes as low as –45 and summers where we were plagued by blackflies and “myggor” — Swedish for mosquitos. There were also lots of references to my dad being away on business trips. My mom was alone for a lot of the time, taking care of the animals and children, and I think she missed having the support of her own mother — just like I do now.

In a letter from December 1982, she asked if her mother “skulle komma till jul och fira” (Could she come and celebrate Christmas with them in Canada?). It’s clear though by the next letter sometime in January that my mormor did not visit.

And I realized, she was probably just like me — overwhelmed and needing her mom. No wonder teaching us Swedish fell by the wayside.

In some ways, this was the message I was waiting to hear. That it’s OK to ask for help. That it’s OK if I’m not fluent in Swedish, because I do have other things to be grateful for. I truly felt like my mom was speaking to me and telling me to appreciate everything that I do have: extended family in Sweden who are supportive of my goal to become fluent, a deep love for Swedish culture. Also, to be grateful that I have kids of my own who might one day be curious about the grandmother they never got to meet.

Antonia Reed is a producer for CBC Radio based in Toronto. She has reported from Thunder Bay to Cape Town and a few places in between. In addition to her Swedish language skills, she knows a smattering of Russian from a year abroad in Moscow and can still remember some of her high school French.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here’s more info on how to pitch to us.