European companies are leading a push into east Asia’s offshore wind market, as they seek to gain a foothold in the region while western turbine-makers still enjoy a technological advantage over their Chinese competitors.

South Korea, Taiwan and Japan have all committed to boost their share of renewables as part of ambitious government net zero targets, while electronics companies including TSMC, SK Group and Samsung Electronics have pledged to achieve 100 per cent renewable electricity in their worldwide operations by 2050.

Jesper Krarup Holst, a partner at project developer Copenhagen Offshore Partners and head of the company’s Seoul office, said that European companies had been attracted by a “fundamental shift” in demand for renewables in Asia, driven in part by US technology giants requiring suppliers to meet renewable energy targets.

“The competition is heating up,” said Holst. “Now we are seeing a push not just from big companies but from consumers and governments as well, while the war in Ukraine has created a huge push for energy security.”

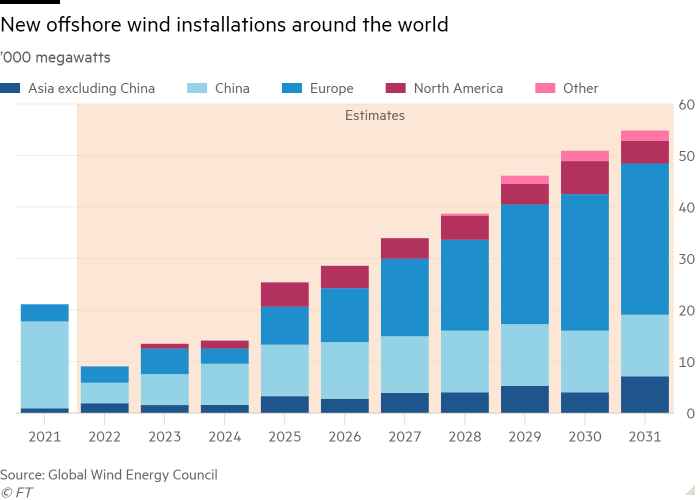

In 2019, there were 5 gigawatts of installed offshore wind capabilities in all of Asia compared with 19 gigawatts in Europe, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena). But Asia is projected to outstrip Europe by the end of the decade, accounting for 60 per cent of global offshore wind capacity by 2050, according to Irena.

Knud Bjarne Hansen, a Danish industry veteran and the co-chief executive of CS Wind, said that “China has perhaps a five to 10 year window to catch up with the turbine technology of the Europeans, so the Europeans need to get a foothold in Asia before that happens.”

South Korea has a national target of achieving 12 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030, up from just 142.1 megawatts at present. Most of the existing capacity is derived from government pilot schemes.

But the process is unwieldy: it currently requires developers to obtain 29 permits from nine different ministries in a process that takes an average of seven years. “The process needs to be streamlined,” said Eunbyeol Jo, a researcher for Solutions For Our Climate, an advocacy group in Seoul.

A Korean wind industry executive said the permit process had given too much power to local politicians, who often grant permits only in exchange for promises of local employment and the inclusion of locally produced components. That has fed inefficiencies and driven up the price of renewables, which in turn has suppressed demand.

One way for foreign turbine makers to navigate some of these hurdles has been to form partnerships and joint ventures with local companies. Denmark’s Vestas has formed a joint venture with Korean wind tower company CS Wind, while GE Renewable Energy signed a memorandum of understanding with Hyundai Electric in February.

Holst said the waters off the east coast of Korea were a perfect testing ground for next generation floating wind towers, which unlike the fixed bottom towers prevalent in Europe, could be installed in waters more than 50-60 metres deep.

“It unlocks huge potential,” said Holst, adding that the presence of Korea’s world-leading shipbuilding industry was an asset in developing and building the massive floating towers.

Meanwhile Taiwan, which has been quicker than South Korea and Japan to reform its energy market to encourage offshore wind projects, began its third round of auctions last month, for site leases totalling 3GW.

In 2020, chipmaker TSMC signed a corporate power purchase agreement, the world’s largest such renewables deal, with Ørsted. The 20-year fixed price contract will give TSMC all of the 920MW generated by Ørsted’s Greater Changhua 2b & 4 offshore wind farm.

Japan, which operates an auction model, is targeting 10 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030, and 45 gigawatts by the end of the next decade. Renewables will account for between 36 and 38 per cent of its power generation mix in 2030, from 20 per cent in 2020, according to its latest energy plan.

But the country’s first big auction in December ended in controversy after a consortium led by trading house Mitsubishi won all three tenders with bids that were much lower than any of their competitors.

Japanese authorities abruptly suspended the process for the second big auction in March this year. People involved in the project said the suspension was in response to concerns that a single player would dominate all of Japan’s biggest projects.

“The Japanese energy market is now likely to be perceived as having an unusually high risk of regulatory change,” said Sumiko Takeuchi, a senior fellow at the International Environment and Economy Institute in Tokyo.

Kohei Amakusa, head of market development in Japan at Ørsted, which participated in the first auction, believes that Japan is still an attractive market among its peers in Asia because of its vast electricity market.

As the Chinese market remains inaccessible for foreign players, companies for now are focusing on the other countries in the region.

“The wind conditions are just as good around Japan and Korea as off the west coast of Denmark,” said Hansen. “The demand is there: no one can exclude themselves from the renewables push.”