Ideas53:59The End of Everything: Katie Mack

Cosmologists aren’t sure how the universe will end, but they’re pretty confident that it will. Since it had a beginning, it will have an ending.

In about five billion years, the sun will scorch the earth to a crisp — unless humans finish off the job before the sun has a chance to.

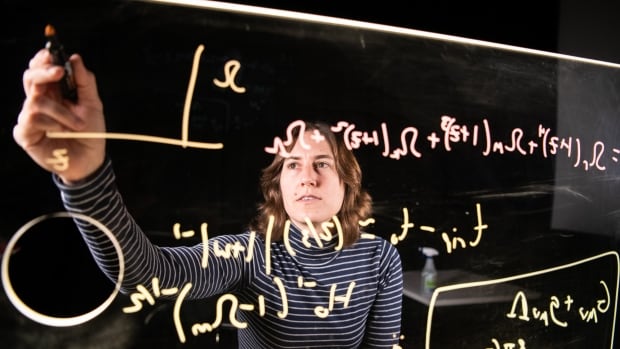

Katie Mack is a theoretical astrophysicist at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario. She studies the possible fates of the universe.

In her book, The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking), she explores the mind-bending science behind different end-of-universe scenarios, and also ponders the meaning of existence when nothing — not even the universe, will last forever.

Mack spoke with IDEAS host Nahlah Ayed about the the theories of the universes eventual demise.

Here is a short excerpt of their conversation:

You talk about the Big Crunch, Heat Death and Vacuum Decay — they all sound so apocalyptic. But there’s another apocalyptic possible fate of the universe that you write about called The Big Rip. Can you explain briefly what that is?

The Big Rip is a possibility where dark energy goes wrong.

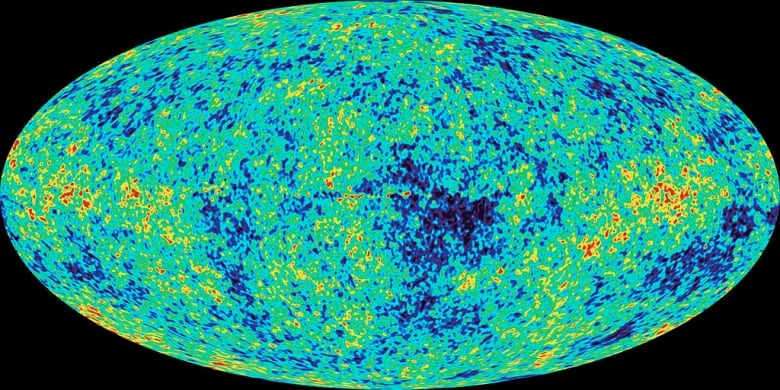

Dark energy is some mysterious stuff that seems to be present throughout the universe, that’s making the universe expand faster. And our best guess at the moment is that it’s a cosmological constant. It’s something that is just a property of space.

But if it’s something that changes over time and gets more powerful over time, if the amount of dark energy and every little bit of space builds up over time, then it doesn’t just move galaxies away from each other, it starts to expand galaxies from within. It starts to build up inside objects, inside bound structures like galaxies and solar systems, but also solid objects like planets and stars.

And you can work out that the way that it acts on the universe as a whole is that it rapidly expands and expands and expands it to the point where you can calculate a date based on certain characteristics of the theory. You can calculate a time in the future at which the entire universe would be ripped apart. That’s the Big Rip.

Though it’s unlikely based on what we understand of how dark energy could work, or our understanding of sort of the possibility of what dark energy could do, but it’s not ruled out by the data. It’s all about understanding dark energy and we don’t understand dark energy. We have some ideas about dark energy, but we don’t know what it is fundamentally.

I wonder what the effect is of working in — and hearing these kinds of possibilities of the end of the universe. I mean, as you say, some of these models have the universe actually lasting for trillions more years. It feels like eternity but it’s not actually eternity. How disturbing or unsettling to you and other scientists and people in general find that to be the idea that the universe just will not last forever?

I went around and asked my colleagues about this as part of the book. I was asking them about the science of these different possibilities and the observations that it’ll take to place limits and that sort of thing. And I made sure in every interview to ask: How does the end of the universe make you feel? Like what does this mean to you personally?

There was a wide range of responses. Some people said that it’s fine, we should be temporary. That’s just part of life. Some people said it was a really disturbing idea — and some of the people who said it was a really disturbing idea were actively working on possibilities that have a continuation of some kind of a cyclic universe.

A lot of people find it very disturbing, the idea that we don’t last forever, even if by forever we’re talking about something so distant in the future that you can’t conceive of it. There’s still something visceral about the idea that all of this will be destroyed. And everything that we’ve seen, everything we experienced will stop and we won’t have a legacy into the future. I think that’s more disturbing about it than other aspects because if I think about my own death, I think, I’m going to die. Everybody dies.

But I will have done something. I will have contributed to my field. I wrote a book. I will have made somebody’s life better, perhaps — and other people might say, ‘I built this amazing building’, or ‘I had children who did amazing things’ or whatever.

People have a legacy that is important to them when they think they’re near the end of their lives. And if the universe is going to end, then none of us have any legacy at all… But at some point, there will be a time when all of human endeavour will have been erased. And I think that’s specifically very disturbing.

You say that is an observation or is that also your feeling?

It’s my feeling, too. I don’t like the idea of it. I don’t want the universe to end — I like it here. So yeah, it’s confronting to me as well. One of the things I talk about in the book is trying to grapple with that myself, with the idea that we don’t last forever and that nothing we do lasts forever.

And what I’ve gotten out of that is that you need to find some kind of meaning in the universe that doesn’t rely on the future. You need to make meaning yourself, have some way of making the universe important and finding a purpose without relying on, you know, ‘Oh, it’ll all be okay in the end’ because it might not.

*Q&A edited for clarity and length. This episode was produced by Chris Wodskou.