Imagine you burn down 20 houses in a village. Then you build 10 houses nearby. Would it be OK to hit the local pub and boast that you’re tackling the housing crisis? Obviously not.

But now imagine that you are a bank. You finance a lot of new coal and oil projects. You also take sustainability seriously: you even have a page on your website dedicated to it! You set emissions targets for 2030, 2040 and 2050 (although, strangely, not many for the time period for which your current board will be held accountable). Could you run adverts lauding your role in tackling climate change?

Well, that’s totally different. It’s how advertising has always worked. You can’t expect the ads to tell the whole story. Are you someone who believes what they see on the side of a bus? (British voters, don’t answer that.)

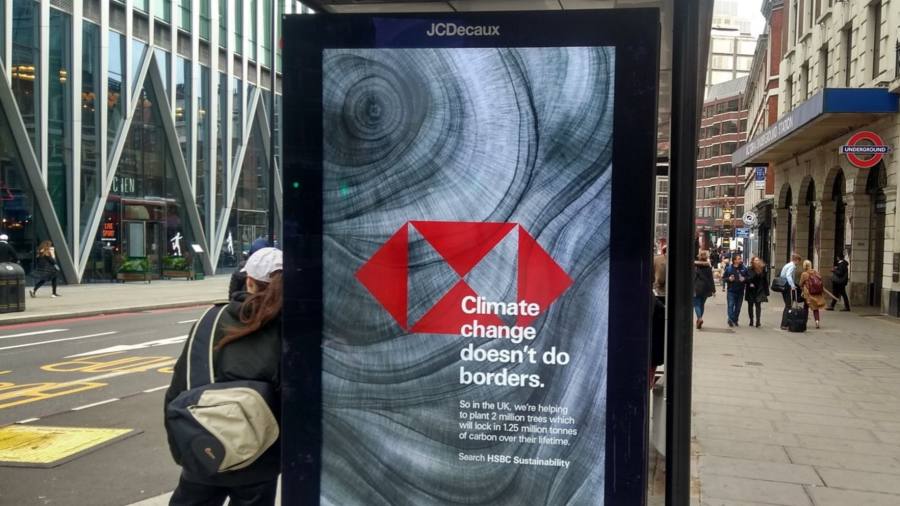

Happily the Advertising Standards Authority, the UK’s advertising self-regulator, this week called out the charade. It ruled that climate posters by HSBC had breached the industry’s code.

The ads mentioned HSBC’s plans to provide $1tn in climate finance and to plant 2mn trees. Literally, they were correct. But the watchdog judged that consumers would assume that HSBC had “a positive overall environmental contribution”, when that is very much unclear. (The bank plans to finance coal mining until 2040.) Put simply, HSBC’s claim was the climate equivalent of the Brexiters’ notion that the UK paid £350mn a week to the EU: it was only one side of the equation.

In the war against corporate guff, the ASA’s ruling is a rare victory. It should mean that companies can no longer cherry-pick random actions as if they were citations for the Nobel peace prize.

HSBC responded that the financial sector has “a responsibility to communicate its role in the low carbon transition”. This misunderstands where we are. As a business, doing your token bit to reduce your carbon impact is like washing your hands after visiting the loo: you don’t get a round of applause. It is as unremarkable as paying your staff (or overpaying your executives). Try revealing your net impact. Or qualifying for a certification. Or stop pretending.

If only the ASA had nipped this in the bud in 2000, when BP branded itself as Beyond Petroleum. The energy company still puts more than 60 per cent of its capital investment into fossil fuels. By comparison, only around 45 per cent of Republican voters are committed to backing Donald Trump in 2024. So the Republican party has got further beyond Trump than BP has gone beyond petroleum.

The ASA alone can’t stop the nonsense. The UK’s advertising code does not apply, for example, to sponsorship. So Qatar Airways was able to advertise at the European football championships with the slogan: “Fly Greener”. The airline pointed me towards its various initiatives, like using biofuels. But given how polluting aviation is, “Fly Greener” was disingenuous at best.

Sports bodies don’t seem to care about who sponsors them: British Cycling just signed a deal to make Shell its official partner until 2030. A few players have had enough. Australian cricket captain Pat Cummins this week made clear he won’t be appearing in ads for the team’s sponsor, Alinta Energy, after suggesting the coal-burning company does not align with his values.

Greenwashing works, because we the public can’t possibly understand every company’s exact environmental impact and can be impressed by big numbers (1mn trees!) and by nice-sounding names — that is, anything beginning with bio or eco. SUVs are advertised next to forests, which makes them seem green.

So anyone who cares about the environment has the regular feeling that they are being hoodwinked. And those companies that are actually making an effort are undermined. Let’s hope that HSBC isn’t the last purveyor of nonsense to get its comeuppance.