Blackstone has emerged as a real estate juggernaut over the past decade, amassing America’s biggest private property empire. But one of the fastest-growing, most lucrative corners has become a quiet concern to some investors and analysts.

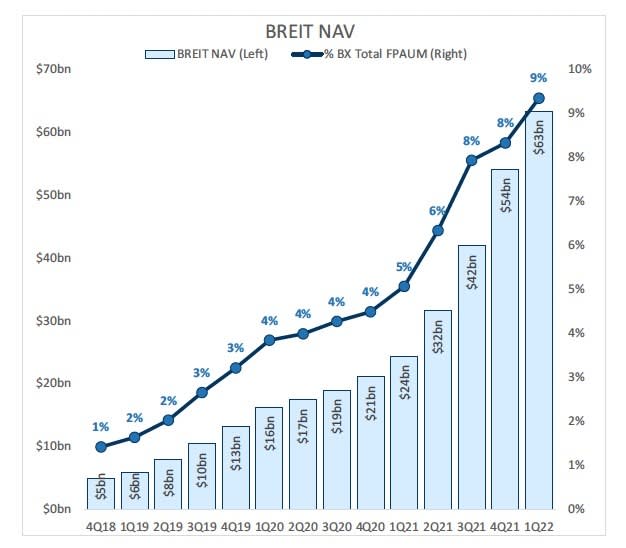

Only launched in 2017, Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust (or BREIT) has grown rapidly. Its net asset value hit $70.4bn at the end of September, according to a filing made earlier this week, thanks to a series of acquisitions, robust performance and wild inflows from income-hungry investors. Add in a decent dollop of leverage and its overall assets have soared to $126bn, a separate fact sheet indicates.

The success of BREIT is a matter of some pride inside 345 Park Avenue. Here’s what Blackstone’s chair and CEO Steve Schwarzman said at the end of Blackstone’s second-quarter earnings call with Wall Street analysts, after detecting a whiff of concerns over the trust.

“I was someplace on Sunday and somebody walked up to me and he said, ‘I’m a BREIT investor. In fact, it’s the biggest thing in my portfolio and I love you people. This is so amazing. All of my friends are losing a fortune in the market and I’m making money.”

It’s a simple story. I’ve been listening to the BREIT discussion and Jon’s laid out our wares pretty well, I think. But the reason we have optimism, where apparently that’s not broadly shared, is that we’re providing enormous value to people who are investors who remember it, and they appreciate the firm. That builds our brand. That helps us raise money. It helps us do our function, which is to underwrite risk and put really good products out, unlike other people where that isn’t the case.

And we’re doing it throughout our asset classes. It’s really exciting to be able to outperform markets by thousands of basis points. And if you don’t think that’s a reason for optimism, then I find that odd. And I think that’s a base that we will be building upon.

Cornball anecdotes aside, BREIT has smashed it, returning on average 13.3 per cent annually net of fees since its birth — including a 9.3 per cent gain in rate-wracked 2022 — and amassed a real estate portfolio that any Gulf royal family would envy.

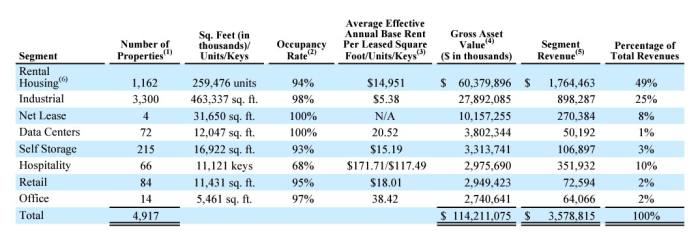

Its $126bn of property-related assets range from a luxury rental apartment complex in Jacksonville, Florida and the JW Marriott in San Antonio, Texas, to data centres in Virginia, student housing in Georgia, industrial properties in Alaska and self-storage depots across Texas.

You can see each of its roughly 5,000 properties online, and below is the overall breakdown (NB, this is as of end-June and doesn’t include some holdings of property-related debt, which is why there’s a discrepancy between the asset value below and the end-September figure given earlier)

Real estate investment trusts are a huge business in the US, allowing ordinary investors to buy a slice of a big diversified property portfolio. The National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts estimates that US Reits collectively own over $4.5tn of property and have a stock market value of about $1.7tn.

However, BREIT is unusual in being a private, unlisted Reit. Most of its peers — like Simon Property Group and Prologis — have shares that trade on a stock exchange.

There was long a bad smell hanging over private Reits. Since they first emerged in the 1990s, the initial sales charge and ongoing management fees have generally been high. Shares are often offered at a fixed price, redemption rights are limited, performance has often been mediocre and lifespans have proved finite. (The law firm Goodwin Procter has a good history of the space.) It was generally seen as a bit . . . unsavoury.

A decade ago the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority issued an “investor alert” warning investors about non-traded Reits, and subsequently fined several brokers for various mis-selling infractions. This added to the sense that serious investment firms should stay away from the space, Morgan Stanley analyst Michael Cyprys told us — at least until Blackstone decided to jump in.

This marketplace was basically perceived as a backwater of the asset management industry, and they really set out to turn it around and bring institutional-grade capabilities in real estate with a much more conducive, aligned fee structure.

So they came in, started investing and putting together this product, and performance was really good. Right before the pandemic they started to really see a ‘hockey stick’ inflection point in terms of receptivity from customers . . . And over the past five-six quarters, the size has taken on a life of its own.

BREIT is now a central plank in Blackstone’s attempt to broaden out from selling its funds to big institutions like sovereign wealth funds and pension plans to “ordinary” (ish) investors. In fact, it’s arguably the central plank in that retail strategy.

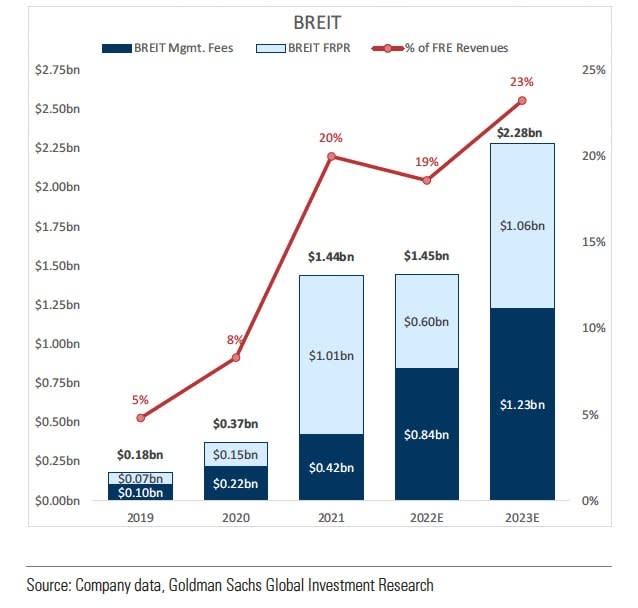

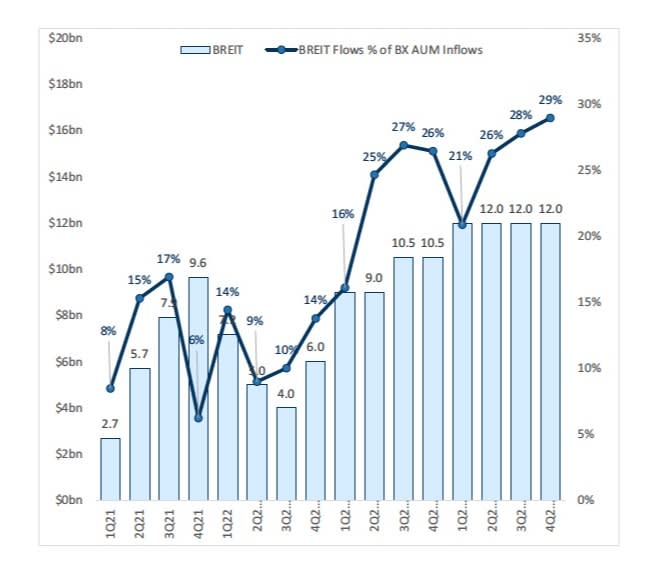

You can see its growing importance in these Goldman Sachs charts, which show BREIT’s explosive growth since 2018 and the investment bank’s forecast for chunky inflows in the coming years as well.

Goldman’s report came out this summer, so its numbers go up to the end of the first quarter (plus its forecasts for the next two years). But we checked the third-quarter results that came out yesterday, and BREIT now represents about 10 per cent of Blackstone’s entire pool of fee-earning assets under management.

Even BREIT’s size actually underplays its rising financial importance to Blackstone. The trust charges a 1.25 per cent annual management fee based on its NAV, and a 12.5 per cent performance fee on its annual total return, (subject to a 5 per cent annual hurdle and a high water mark). Given its swelling heft and returns, the trust has become a gold mine for Blackstone.

Last year BREIT threw off $1.44bn in fees and alone accounted for about a fifth of Blackstone’s overall fee revenues, according to Goldman Sachs (Blackstone doesn’t seem to break out its fee revenues from BREIT). Goldman forecasts that this could rise to $2.3bn and 23 per cent of Blackstone’s fee revenue by the end of 2023.

By almost any measure, BREIT is an incredible success story for Blackstone (one that rival executives talk enviously about). It’s no surprise that photos of the company’s president Jonathan Gray are plastered over BREIT’s website and investor documents.

After all, it’s the kind of big win that makes Wall Street careers — perhaps even solidifying a candidate as Schwarzman’s heir apparent. Here’s Gray talking about his “beloved BREIT” earlier this year.

“Our thought was ‘what if we took the most successful largest real estate investment business in the world and delivered it to individual investors and charged essentially what we charged institutional customers? Wouldn’t that be a tremendous product?’ And that was the basis for BREIT.”

However, FT Alphaville cannot help but wonder if BREIT might be facing a far less hospitable environment over the next few years. In fact, it looks downright nasty. And the trust is now so big that any setback would be meaningful for Blackstone more broadly.

Firstly, these kind of yield-generous products — BREIT’s annualised distribution rate has been 4.4 per cent since its birth in 2017 — were like manna for investors in the low interest rate era. When BREIT launched, the average global bond yield was just 1.7 per cent, making it obviously attractive as an alternative to investors who craved a steady income stream.

But a one-year Treasury bond now yields 4.6 per cent, which is more than BREIT currently throws off. Investment grade US corporate debt yields 5.9 per cent and junk bonds yields are approaching 10 per cent. The inflation-triggered rise in fixed income yields is a seismic change to the attractions of Reits and a host of other “bond proxies” that have done well in recent years.

At the same time, rising interest rates are a huge threat to the US real estate market, and especially housing. Americans are blessed with the marvel that is the 30-year fixed mortgage, so rising rates take a while to bleed into property prices. But look at how the average cost of a 30-year mortgage has rocketed this year.

From about 3 per cent at the start of the year to nearly 7 per cent! That’s going to hurt a lot of the frothier regional real estate markets that took off after the pandemic. And housing makes up 52 per cent of BREIT’s portfolio. Rising rates are also going to hurt commercial real estate, large swaths of which have already been battered by the work-from-home trend and also make up a decent chunk of BREIT’s holdings.

The combination of more yield-generous investment alternatives and the possibility of a potentially wide-ranging property downturn is obviously not great news for real estate investment trusts like BREIT.

Are there any public-market proxies for what the market thinks the outlook might be? Conveniently, there are. Goldman Sachs reckons that BREIT’s geographic tilt towards residential property in the American ‘Sun Belt’ means that Camden Property Trust and Mid-America Apartment Communities are the best public equivalents.

Look at what their share prices have done over the past year compared with BREIT’s net asset value.

Obviously, NAV vs stock price is not a great comparison — dual axes yada yada — and BREIT has hardly been immune from the budding real estate downturn. As a footnote in a recent performance update obliquely says:

BREIT has incurred $702.2mn in net losses, excluding net losses attributable to non-controlling interests in third-party JV interests, for the six months ended June 30, 2022. This amount largely reflects the expense of real estate depreciation and amortization in accordance with GAAP.

Is this just the beginning, as rising rates deflate the US real estate market, reverse the employment boom and dampen appetite for yieldy investment products like BREIT?

Having talked to a few prospective investors in recent months it’s clear that some are wary of BREIT for exactly these reasons. Even Goldman’s note this summer mentioned that the investment bank had . . .

. . . fielded an increasing number of questions from investors on the back of growing concerns around BX’s BREIT fund including: a) markdown risks in light of deteriorating performance of publicly traded REITs and wider cap rates, b) BREIT’s significance in the context of BX’s growth, and c) the potential impact on BX earnings and share price from a moderation of BREIT flows.

Judging from the analyst questions on Blackstone’s earnings call — several of which explored BREIT specifically — these concerns have not gone away since. So FT Alphaville spoke with Frank Cohen, a senior managing director at Blackstone and BREIT’s chief executive and chair to better understand the business and its own outlook.

Cohen said out that Camden and MAA might be roughly equivalent to BREIT’s residential portfolio, but argued that it was more diversified and owned better regions, making them poor public-market proxies for BREIT. Moreover, Cohen pointed out that rising interest will make mortgages less affordable to many households, and said this would boost the rents that Blackstone can charge (many of its leases are short-term and can be jacked up regularly).

Fundamentally, he argued that vehicles like BREIT were well placed for the current economic and financial outlook.

“Our job is to constantly evaluate the portfolio. At any given time we are both selling and buying. It is constantly changing . . . Everything we buy is oriented towards growth. Real estate is a great place to be in an inflationary environment so long as you pick the right sectors. I’m not saying growth will continue at the same rate through a market slowdown, but the fundamentals in our sectors remain strong and we’re very well positioned.”

In its latest filing BREIT said it has a leverage ratio of 46 per cent and $9.6bn of quickly-available capital to handle any outflows and take advantage of opportunities. As Cohen told us: “We also run our business with a massive amount of liquidity both for offence and defence.”

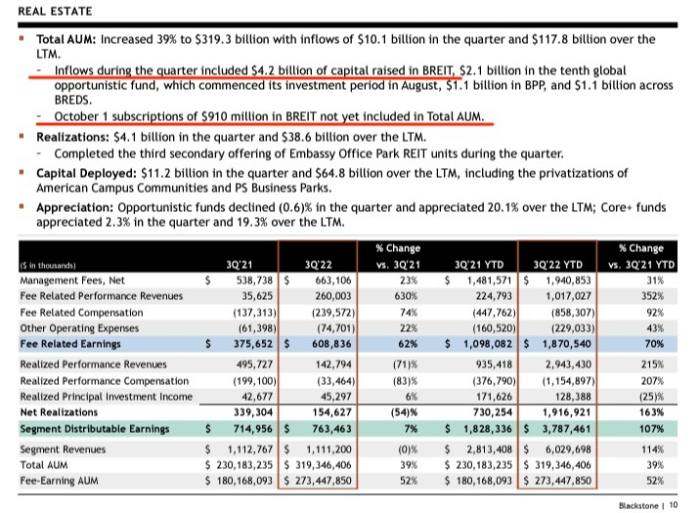

And to be fair, it seems that BREIT is (so far) only seeing a slowdown in inflows. Blackstone said in its third-quarter results that the vehicle enjoyed inflows of $4.2bn over the three months, and another $910mn shortly after the quarter ended. Given current market conditions, that’s impressive.

Nonetheless, given the investor-tempting headline returns that BREIT still boasts, we probably won’t get a proper sense of its true durability until the value of its real estate markets get properly marked down (and private market marks move slowly, especially in real estate).

Performance might then start to look very different, and we will start to see how sticky the torrential inflows of the last few years really are, and whether rental income can outpace any drop in the value of its assets.

Blackstone’s beloved BREIT could still end up becoming a bloody headache.