In the run-up to its hotly anticipated IPO, UK-based chip design company Arm has resorted to a risky strategy: suing one of its biggest customers. But with the dispute hinging on how revenue from new markets for its technology should be shared, it may have had little choice but to go to court.

The lawsuit, filed in district court in Delaware in late August, accuses mobile chip technology company Qualcomm of using Arm’s intellectual property without permission. The case stems from Qualcomm’s $1.4bn purchase last year of start-up Nuvia, which designs chips based on Arm’s technology.

The acquisition highlighted the technology interdependence of Arm and Qualcomm, with both companies searching for markets in which to expand beyond the mature smartphone industry. Nuvia’s first design was for an Arm-based chip for use in data centres, though Qualcomm has said it wants to use the same design to break into other new markets where Arm’s technology has yet to get a large foothold, including laptop computers and cars.

Arm is dependent on customers such as Qualcomm taking its technology to new markets because it “needs a growth story” to attract investors to its expected IPO next year, said Stacy Rasgon, an analyst at Bernstein Research. “If it’s just a smartphone story, it won’t go well.”

However, after months of disagreement over the terms on which Qualcomm could use the Nuvia technology, Arm turned to the courts. It claims that the licence it issued to Nuvia was not transferable and demanded that Qualcomm destroy any intellectual property that it assumed in the acquisition.

Qualcomm responded with a claim that the Nuvia technology was covered by an Arm licence that Qualcomm itself took out some years ago, and asked for a summary judgment dismissing the case.

The dispute has shone a spotlight on Arm’s complex licensing arrangements, which in some cases leave it in direct competition with its customers. In the process, it has revealed a potential challenge to Arm’s business model as some of its biggest customers take more of the chip design process in-house in search of new ways to differentiate their devices.

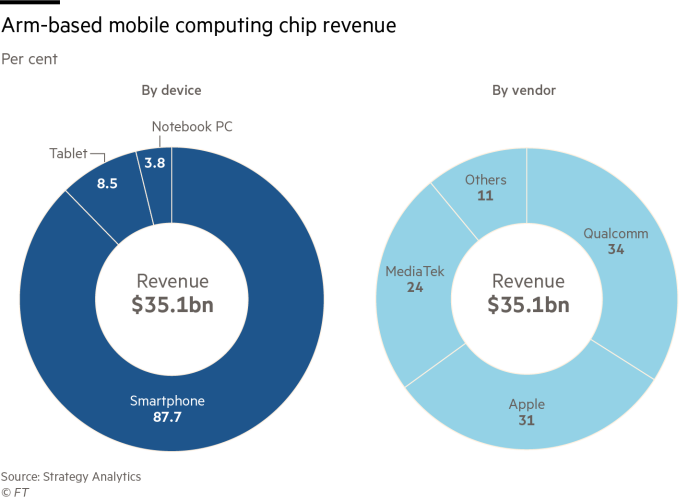

Last year, Qualcomm was the biggest seller of Arm-based chips for use in mobile computing devices, where Arm’s low-power chip designs have been most successful, according to research firm Strategy Analytics. It estimated Qualcomm sold $12bn of the $35.1bn worth of Arm-based chips used in smartphones, notebooks and tablets. That was just ahead of the $11bn of chips that Apple designed for its MacBooks and iPads using Arm blueprints.

Arm’s royalties come from two types of licence. One, known as a technology licence, covers sales of Arm-designed computing cores — the central “brains” of a computer processor. Qualcomm buys Arm’s Cortex cores for use in its Snapdragon smartphone processors.

Arm’s other type of licence covers only its basic chip architecture. Nuvia, one of around a dozen companies to have this kind of licence, uses it as a foundation for designing its own computing cores.

Arm negotiates different terms with each customer and does not disclose its licensing rates, but royalties under a technology licence are generally higher because Arm itself puts in the extra work of designing the cores. Arm’s non-royalty income — upfront payments it negotiates when signing a new licence — jumped 61 per cent last year. But its $1.54bn of royalties, which were up 20 per cent, still account for 58 per cent of its revenue.

Sravan Kundojjala, an analyst at Strategy Analytics, estimated that Qualcomm pays Arm an average of about 80 cents for each of the 350mn to 400mn chipsets it sells each year, using Arm cores. Qualcomm would probably save 40 per cent to 50 per cent on its royalty payments if it replaced these with Nuvia’s Phoenix cores, he added.

Qualcomm said in a legal response to Arm late last month that with Nuvia’s technology, it would be able to compete directly with Arm, as well as with other Arm licensees and companies that use the rival Intel x86 chip architecture. It also said it expected to use the Nuvia cores in the all-important smartphone market that makes up much of Arm’s existing business.

Qualcomm is not alone in taking on more of the chip design process to gain an extra edge for its products. Apple, which has also developed its own computing cores under an Arm architecture licence, surprised the tech world with the performance of its first M1 chips, which were introduced two years ago.

Another big customer, Nvidia, agreed to pay $750mn for a broad licence to Arm’s technology when it tried to buy the company in 2020. That deal also included an architecture licence, though Nvidia recently said it would use Arm’s Neoverse cores for its latest data centre chips.

With some of the biggest chip companies putting more effort into creating their own computing cores under architectural licences, “it looks like licensing rates are going down for some of [Arm’s] customers”, said Rasgon. “Potentially, you have a lot of their customers who are moving to a royalty-based model that isn’t worth as much.”

Bob O’Donnell of TECHnalysis Research added that the shift could force a rethink about how Arm charges for its intellectual property. “Some have argued Arm hasn’t charged enough in the past. Arguably they need to raise the price of their architectural licences,” he said. Adding to the potential pressure on the company’s revenues is the fact that Arm’s business is highly concentrated, with around a fifth of its customers accounting for 80 per cent of its royalties, according to Kundojjala.

Legal brinkmanship over important intellectual property rights ahead of an IPO is nothing new. Yahoo sued Google over a patent it owned on search advertising before Google’s IPO in 2004, forcing a settlement. For Arm, the pressure is now on to show potential investors it can maintain its royalty rates as it looks ahead to a new phase of growth.