“Common ownership” is a controversial theory that has been making waves in financial academia, which argues that big institutional investors and asset managers that own shares across an industry stunt competition.

This is about incentives, not dodgy deals made in smoke-filled boardrooms. In other words, if you run a company and know your biggest shareholders are also the biggest shareholders in your rivals, perhaps your competitive instincts are blunted just a little?

The classic example of airlines is somewhat let down by the aviation industry’s infamous tendency towards bankruptcies. Richard Branson once joked that the best way to become an airline millionaire was to be a billionaire and invest in aviation. Naturally, big investors have very aggressively pooh-pooh’d the idea.

However, Barclays has found an intriguing example that is likely to make the waves even bigger and reach much further than mere academia — the US energy industry.

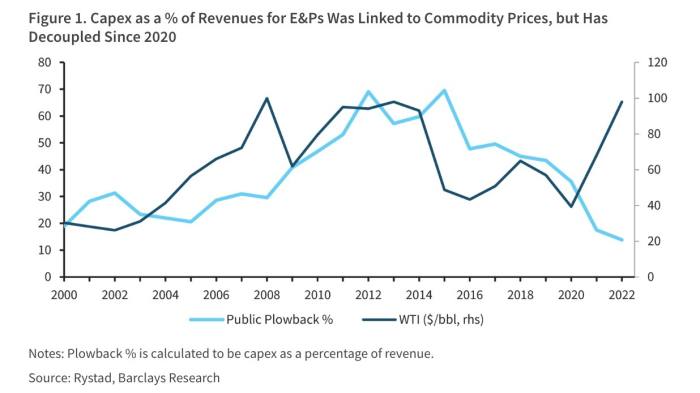

Despite soaring oil and gas prices, it seems energy companies are not drilling. The link between investments and commodity prices has been broken since around 2020, notes the report lead-authored by Jeff Meli, Barclays’ head of research.

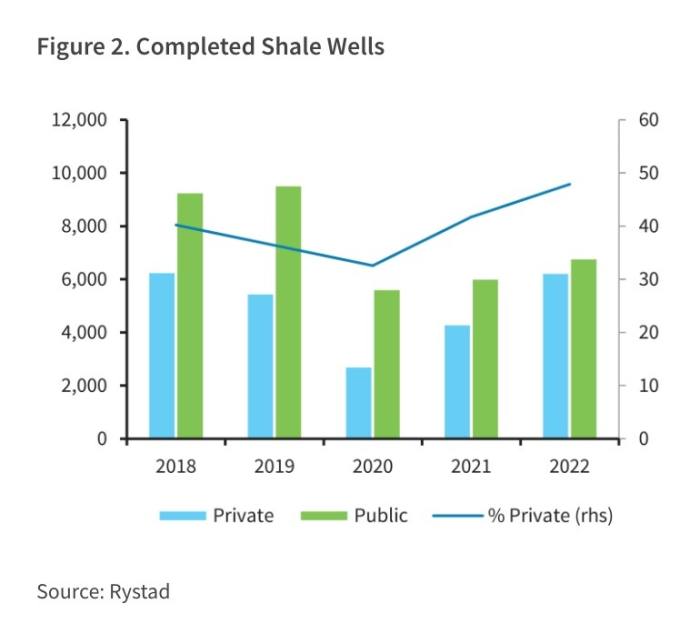

Intriguingly, this is not true for privately held energy companies. In fact, private producers have completed nearly as many wells in 2022 than their bigger public peers, and now operate almost 60 per cent of all US rigs, according to Barclays.

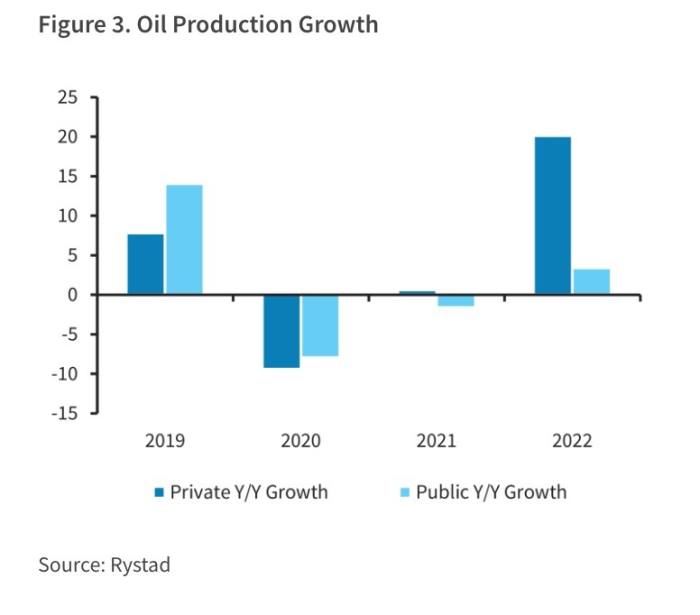

The bank estimates that public energy companies are growing oil production at an annual growth rate of about 5 per cent this year, while private ones are expanding at a 20 per cent clip.

What could be causing this discrepancy? Barclays reckons that it could be the explosive growth of passive investor ownership across the listed energy sector.

As a percentage of overall investment fund ownership, passive funds have gone from 10 per cent at the start of 2010 to over 30 per cent at the end of March 2022. Here we want to quote at length from the report:

The energy market could be experiencing a similar phenomenon [to the one found in the airline industry]. A singular energy company that increases drilling in response to higher crude prices benefits from its greater production. However, if all energy companies increase drilling, then there is potential for the cumulative increase in supply to weigh on prices, reducing the profitability of the additional activity. Widespread drilling could also result in higher prices of equipment, labor, and other inputs, further depressing profitability. Put differently, drilling in response to higher prices could resemble a classic prisoners’ dilemma: companies are better off collectively if drilling is limited, but each company has a strong incentive to take advantage of higher prices on its own, and the result is that all companies react to higher prices by increasing production.

Of course, the classic prisoners’ dilemma presumes that companies cannot coordinate. But common ownership, particularly by passive investors, could facilitate common operating strategies by reducing the number of different stakeholder views conveyed to management. Moreover, some studies have found that hedge fund activism declines as passive fund ownership increases.

For passive investors, the benefits of one public energy firm competing aggressively — for example, by increasing drilling activity — could come at the expense of other public firms that are part of the same investors’ portfolio, thus reducing total portfolio value. Hence, they might prefer that all companies avoid taking advantage of higher prices. This hypothesis is consistent with the anecdotal refrain we hear from energy companies saying that their large equity holders are favouring returning free cash flow to investors rather than increasing production.

Private companies, which by definition have zero common (passive) ownership, are not affected by this dynamic and, thus, have a greater incentive to tap into higher energy prices by increasing their drilling activity.

Now, this could just be that public producers are simply more disciplined on capital than old-skool oil barons who whisper “drill baby drill” in their sleep.

Even Barclays notes that the management teams of oil companies have told them that there is a general “shareholder preference” for maximising free cash flow rather than production growth.

Or as someone pithily said about Harold Hamm’s bid for Continental:

For the 25-year old with a global crude S/D model out to 2040, there is one thing you must understand:

Your spreadsheet is absolutely no match for the one-two punch of wildcatter bloodlust for black gold paired with disdain for allocating capital responsibly.@InnocenceCapit1 pic.twitter.com/hli9zw6lxv

— Bear Force 1 (@BearForce_Won) October 17, 2022

In fact, it might even be good for longer-term shareholder returns and the energy industry as a whole, as on aggregate it could make it less prone to boom-and-bust cycles caused by gluts of over-investment whenever prices are high.

It also mirrors a broader push for big mature public companies to plough more of their money into buybacks and dividends rather than capex. That is arguably caused more by activist investors than passive funds (which eschew getting stuck into management’s capital allocation decisions).

It could also be related to the whole global ESG push, a phenomenon that overlaps with but really is separate from the explosion of passive investing.

Yes, BlackRock’s Larry Fink has been a loud advocate for using shareholder power to address the climate crisis, but he came to the ESG wave later than many other big institutional investors. And Vanguard — the second-biggest passive investor globally, but bigger in the US than BlackRock — has been notably more circumspect on how aggressively it will act on ESG.

But this topic is not going away, and certainly not now that Barclays has opened up a new front in the more politically-charged US energy sector. It’s very easy to see how some Republicans will seize on this, but they are not the only ones that have seized on the common ownership theory.

Even the FTC and European Commission have begun to take an interest. As Harvard Law School’s Einer Elhauge wrote back in 2019 in reviewing the growing body of work in the field:

Horizontal shareholding poses the greatest anticompetitive threat of our time, mainly because it is the one anticompetitive problem we are doing nothing about. This enforcement passivity is unwarranted.