On an exposed ridge deep in Appalachia, 23 shining new wind turbines loom over a wooded valley — the newest additions to the energy mix in America’s traditional coal heartlands.

The Black Rock wind farm, nestled in the remote mountains of outer West Virginia, is exactly the sort of project President Joe Biden hopes will proliferate as a result of the unprecedented clean energy cash injection he signed into law in August.

The president wants to ignite a green revolution that will transform the American energy landscape, slash carbon emissions and put the country at the forefront of a global cleantech race. But more than that, Biden also promises his $370bn clean energy push — under a law named the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) — will bring new jobs to depressed fossil fuel communities where livelihoods depend on the extractive industries.

Nowhere is the fallout from the decline of old energy more pronounced than in West Virginia — the country’s most coal dependent state — where the demise of a once vibrant sector has upended the local economy, with almost one in five people now living in poverty.

But West Virginia remains coal country. And on the ground, the prevailing sense is not that an energy transition is a route out of Appalachian misery, but an assault on an identity and way of life.

“Dude, we barely even got any damn Tesla fuckin’ chargers in this state,” says Jonas, a 22-year-old construction worker, outside the Piggly Wiggly grocery store in Charleston, the state capital. “It’s definitely — definitely — a coal state through and through.”

“I don’t know that we’ll ever become a green state,” says another shopper, a retiree who declined to give his name. “For West Virginians,” he says, “It’s: ‘My great-granddaddy was a coal miner; my granddaddy was a coal miner; my daddy was a coal miner; I’m gonna be a coal miner; my son will be a coal miner.’ It’s this philosophy of ‘we cant change’.”

Yet it is the buy-in of people in fossil fuel-producing states such as West Virginia that Biden needs most if his green revolution is to succeed.

This was the state that did more than any other to shape Biden’s climate law. It was Joe Manchin, the state’s obstructionist Democratic senator, who ultimately signed off on Biden’s climate plan — casting the deciding vote.

No individual embodies the tension and complexities at the heart of the energy transition as much as Manchin, a Democrat who has been elected to the US Senate three times in a Republican stronghold state that twice voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump. No senator holds a tougher seat.

That goes some way to explaining why Manchin is no climate evangelist. As governor, he sued the Environmental Protection Agency for blocking mining permits in his state. Campaigning for a senate seat, he shot a bullet through proposed carbon pricing legislation. And in December, he scuppered Biden’s initial plans for a climate spending spree, via the $1.75tn Build Back Better bill, on inflation concerns.

To the surprise of many, though, he ultimately came around, backing a slimmed-down version of the package in the guise of the Inflation Reduction Act. In doing so, he effectively greenlit a bill designed explicitly to speed the expansion of green energy — and displace coal.

The coal industry was furious. “West Virginia will suffer,” says Chris Hamilton, president of the West Virginia Coal Association and a former mine foreman. “West Virginia’s coal industry today has a limited timeline placed on it because of this legislation.”

But if the bill can succeed here, in the heart of coal country, in providing lasting alternative employment to mining, it has the potential to be transformative in driving an energy transition across America.

To do that it needs to create new opportunities that ensure buy-in at every level, says Elizabeth Ruppert Bulmer, lead economist at the World Bank. “It cannot be a case of: let’s pay everybody off, and we’re done; we close the mine and turn the key and walk away,” she says. “We’ve got to transition to an economically viable and inclusive development model.”

Coal’s rise and fall

Appalachia’s coal mines are fundamentally entwined with US history. They fed the furnaces that industrialised America in the 19th century, forging the iron and steel to build ships and trains. Later they powered the war effort, allowing the mass production of rifles and tanks that won two world wars

“It’s coal country,” says Jerry Coleman, who spent 37 years down the state’s coal mines, before contracting black lung, a debilitating respiratory illness. “You go back as far as you want and West Virginia has produced coal. Coal is West Virginia. You’ll never phase it out.”

Like thousands of other local men of his generation, Coleman’s father contributed to the wartime effort not on a far-flung European battlefield, but down the Appalachian mines. “They wanted him to stay in the coal mines to produce steel,” he says. “That’s how important coal was.”

For people in the Mountain State, the industry is a source of both pride and identity. Many tell stories of relatives who flocked to its hills and valleys during the boom years drawn by the promise of work. Its southern counties are strewn with the remnants of “company towns” built to house miners and their families in remote areas. Even the state flag features a pickaxe-wielding miner.

In the 1970s, as the Opec oil crisis rattled the US economy, President Jimmy Carter made coal a centrepiece of his energy strategy, promoting the fuel as a solution to dependence on foreign supplies. Domestic reserves such as those in West Virginia and Wyoming would help America keep the lights on.

Today, the industry is in terminal decline — both in West Virginia and across the US. Shifts in technology and efficiency have contributed to a steady fall in employment since the middle of the last century.

During the second world war, more than half a million people were employed in America’s coal mines, 130,000 of them in West Virginia. Today the national figure is about 60,000. In West Virginia it is less than 12,000 — its lowest level since 1890.

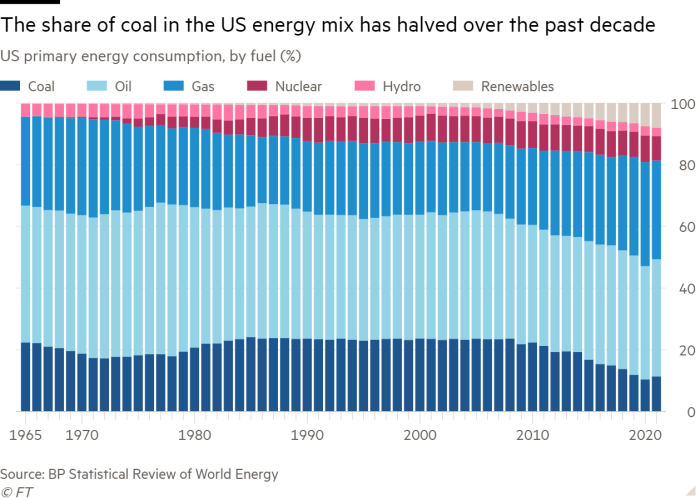

But it was only in the past decade that production hit a wall, after peaking in 2008. The main culprit was not environmentalism, but the shale revolution, which provided an abundance of cheaper, cleaner natural gas, replacing coal as a fuel in power plants; more recently plummeting costs for wind and solar have added to the malaise.

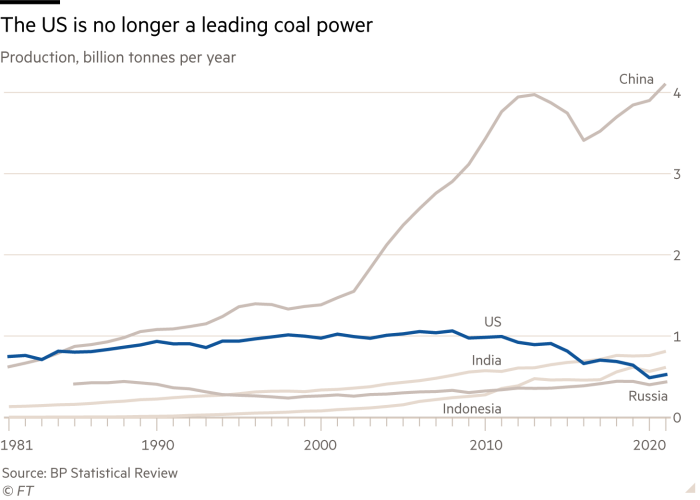

America produced more than 1bn tonnes of coal a year at the turn of the century, accounting for a fifth of the global total and second in volume only to China. Last year, it was roughly half of that. In West Virginia — today the nation’s second biggest coal producer, after Wyoming — it has halved from its 1997 peak, sitting at a little more than 80mn tonnes last year.

“The reality is we never should have let ourselves become so completely addicted to just one industry,” says Brandon Dennison, chief executive of Coalfield Development, which retools former West Virginia miners and puts them to work in start-ups. “But we did — and that one industry went into a rapid decline.”

Unemployment shot up in coal communities, contributing to and compounding an opioid-addiction epidemic that ripped through the state. Today, West Virginia has the lowest labour force participation in the country at about 55 per cent, 6 points below the national average. “The bottom fell out,” says Dennison. “It just felt like economic freefall.”

Thriving in new ways

In 2016, the coal industry welcomed a potential saviour: Donald Trump, who vowed on the campaign trail that miners would be “working [their] asses off” if he won the presidency.

In West Virginia, two out of every three voters backed Trump’s successful White House bid, higher than any other state. Yet despite his pledge, American coal jobs continued to slide — falling from 51,000 to 38,000 during his term.

Trump may be gone, but the industry and local politicians are still raging against coal’s decline — and doubling down on its use.

When the state’s two big utilities sought to shutter uneconomic plants, the Public Service Commission of West Virginia ordered them to keep them open and shifted the facilities to a regulated rate base, leaving consumers to prop them up.

Even gas-fired power plants have struggled to gain traction in the state. Last year, the commission ordered the state’s utilities to run their coal plants at historical levels — even in cases where it was cheaper to buy in power generated elsewhere from gas or renewables.

Coal’s dominant position on the state grid, producing 90 per cent of its electricity, leaves little space for renewable developers. Governor Jim Justice, a coal magnate who has the word “Coal” on his personalised licence plate, has said it would be “frivolous” to think that “windmills are just going to take over and be our salvation”.

Yet the incentives in the IRA could be “potentially huge for West Virginia,” says James Van Nostrand, director of the center for energy and sustainable development at West Virginia University. “But we don’t have the policies at the state level that say: ‘Bring it on, we’re open for business and the clean energy economy’ . . . that sign was not lit in West Virginia.”

In deciding to back the package, Manchin was sending a critical message to his state: that coal is not coming back — and West Virginia needs to move on. “Inaction will not reverse the trends that we have seen in the coal industry,” he wrote in a letter to coal bosses.

“I will not apologise for taking action to give this industry and our coal communities every opportunity I possibly can to survive and thrive in new ways.”

At the heart of the IRA is a system of tax credits designed to spark a mass buildout of wind, solar and energy storage projects across the country. The US energy department says it will cut emissions by one gigatonne a year and put the country within sight of its commitment to slash emissions to half of 2005 levels by the end of the decade.

Manchin ensured the tax credits would steer this investment towards states such as West Virginia, boosting the payout if clean energy developers site projects in fossil fuel communities.

“This is a really important way to make sure workers are not left behind,” says Leah Stokes, a political-science professor at UC Santa Barbara. “I can understand why folks might be sceptical but give it a minute and folks will be surprised.”

Yet traditional renewables were not Manchin’s priority. The deal ultimately carved out by the senator pumps funds into carbon capture, an old technology yet to achieve scale that proponents hope could prolong the lives of fossil fuel gas and coal burning power plants.

The bill also supports the development of hydrogen, a new fuel source that could be produced using natural gas and coal; and it seeks to drive a boom in green manufacturing, supporting domestic plants that build electric vehicles and their parts.

To Hamilton, representing the coal industry, the legislation backed by Manchin does little more than bankroll coal’s rivals. “When you bring in a new source of power, the chances are that it will result in some lower amount of coal-based generation,” he says. “We’re asking, here in West Virginia, for coal miners to expend some of their tax dollars to support competitive fuels aimed at putting them out of business.”

A greener future

Despite the opposition, renewable developers are making big plans for West Virginia. Clearway, the company behind the five-month-old Black Rock wind farm and the biggest clean energy player in the state, intends to increase its operations there by a factor of five — with two gigawatts of projects in the works, which are roughly equivalent to two nuclear reactors or enough to power 1.5mn homes.

“The state has sat at a crossroads for America’s energy needs for a century,” says Craig Cornelius, chief executive of Clearway. “I think of renewables as the next category of energy that West Virginia will produce for itself and export to its neighbours.”

Politicians such as John Kerry, Biden’s top climate diplomat, have insisted coal miners will find jobs in the new green economy — erecting wind turbines, for example, or installing solar panels.

The problem is that unlike coal, renewables are not a big employer — at least after construction is finished. The Black Rock wind farm created 200 jobs during the construction process, but today it takes less than a dozen technicians to keep the facility ticking over.

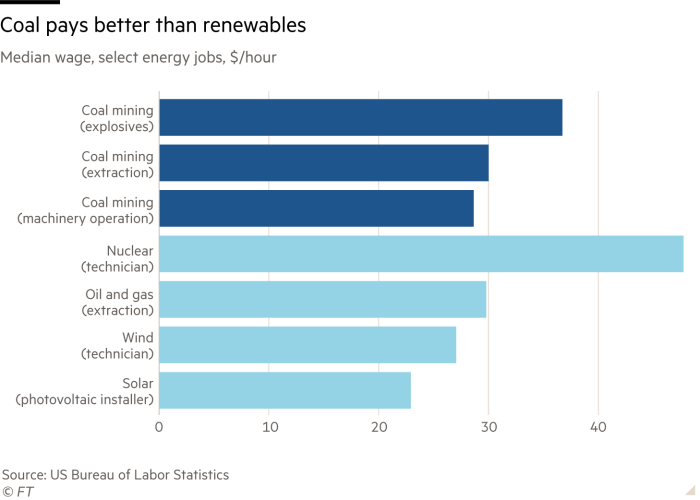

Coal pays better, too. The median wage for a miner is $30 an hour — rising to about $37 if you handle explosives, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. That compares to $27 for a wind turbine service technician and $23 for a solar panel installer.

Manufacturing, however, is more job-friendly — and has been welcomed by the state. At least eight big green manufacturing announcements were made in West Virginia this year.

Among the companies the state has drawn in is GreenPower, an EV start-up setting up the state’s first electric vehicle manufacturing plant in South Charleston. Beginning production this autumn, by next year it will churn out up to 50 electric school buses a month.

Sitting in a bright yellow prototype bus, chief executive Fraser Atkinson says the state has bent over backwards to accommodate his company — purchasing a work-ready site for it and subsidising each local hire made. The IRA, he says, will “kick-start and probably turbocharge” commercial electrification — including in West Virginia.

Sparkz, a California battery start up, plans to build a manufacturing plant in Taylor County, in the north of the state. The factory will hire and retrain former coal miners, under a deal with the United Mine Workers Association hatched at a White House dinner.

Cecil Roberts, head of the UMWA, said the IRA’s incentives to “build plants in the coalfields” would be “a big step toward providing good jobs to these distressed communities” as he threw his weight behind Manchin this summer.

“It feels to me like we’ve sort of gone through the stages of grief with coal,” says Dennison, Coalfield Development chief. “There’s been a lot of anger and denial a few years back. But I think it’s starting to set in that — it’s not going to totally vanish overnight — but it’s also never going to be the giant that it was.”

“And if we want to survive, we’re going to have to accept that and start to figure out some different things.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here